Serena Korda’s practice spans sculpture, performance and installation and has 'world-building' at its core. Serena reviews historic and mythic narratives through a feminist lens, reworking them to create her own idiosyncratic mythology. Serena’s work was included in the survey show Strange Clay: Ceramics in Contemporary Art at the Hayward Gallery, 2022-23, and her recent solo show The Maidens opened at Cooke Latham Gallery in Feb 2023. In this interview with Fay Nicolson, Serena discusses the themes and concerns that have weaved throughout her practice, the shifts that have occurred during her prolific career, and the new works emerging fresh from her kiln.

Here's one I made eariler...

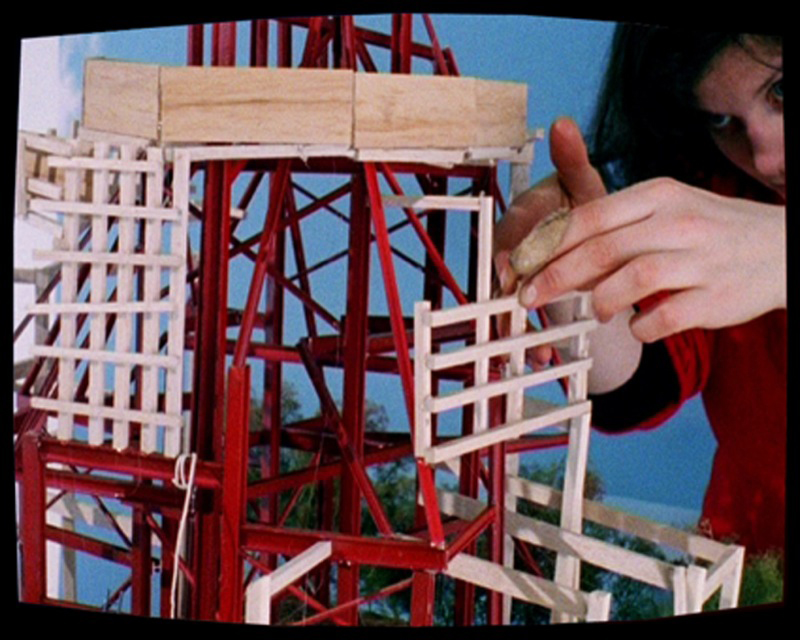

Hi Serena, I first came across your work in your RCA MA Show around 2008. I was exploring the power of documentation and fiction at the time and was blown away by your installation ‘Building the Matterhorn’. I loved the rich, intertextual installation across image, video, object, and publication – and your work encouraged me to apply to the Printmaking course to do my MA. Why did you gravitate to that specific course after your BA at Middlesex and have you ever considered yourself a Printmaker?

Aww thanks Fay, so lovely to hear you encountered my work at the MA show and it inspired you to apply for printmaking. I was aware that several people with interdisciplinary practices had been accepted onto the printmaking course as it was known for being experimental and about “expanded printmaking”, so it felt most affiliated with my multidisciplinary approach at the time of applying. At Middlesex I had never specialised in any one medium. The course nurtured performative and multidisciplinary approaches and that’s what I love about art making; that it didn’t need to be categorised or fit into a box. So, when applying for the MA I wanted to be on a course with a similar energy and ethos. I had never done any printmaking but I was very involved in how I could make the ephemeral part of my practice (which was performance) tangible through print and publication, making the actions visible and live beyond the event. I was aware of the history of disappearance that performance art breeds and at that stage was fascinated by how objects and texts from performances could be more than props. The objects could tell the tale of their own making, creating their own mythology and sense of animism.

Serena Korda,'Building the Matterhorn', 2009, MA Degree show at the RCA, installation view.

Performance to camera

You are currently working with ceramics and often post videos online revealing insights into your making process. After watching one of these on Instagram I thought of your early video ‘Building the Matterhorn’ and how these both deal with the (de)mystification of making art. What are your motivations for making these WIP videos and do you see them as part of your practice?

I really love this question, it is so perceptive and brilliant that you see a relationship between my older works and how I am performing to camera for Insta. My process is integral to my practice, I think through making and the Instagram account has always been there as a way of showing some elements of my process. But it was really when I deep dived into using clay and making during the pandemic and after having a baby that I used this platform as a way (the only way I had) of connecting with my audience and staying visible. The pandemic isolated all of us but I was feeling this dislocation between my practice and me in the early days of motherhood. Making things is part of the fabric of my existence; it’s what fuels my creative energies and what keeps me going as a human. I knew I couldn’t give this up but had to find new ways to adapt and work with what time I had to put into this side of my world. So, late night Instagram making videos evolved and have stayed not only as a way of connecting people to the intricacies, highs and lows of this involved and complex process, but it also became an extension of the socially engaged practices that had been integral to my work for so many years.

Serena Korda,'Building the Matterhorn', 2009, video still.

During the pandemic certain institutions were exposed as places of bad practice in the way they worked with artists and other cultural workers. They have really been held accountable and forced to turn their practices around so I was quite aware I didn’t want to return to the same ways of working. But it was also time for me to nurture my own studio practice and step into a more autonomous world which didn’t have collaboration at its core. I needed a singularity of voice as I had a third of the time I used to have pre-motherhood, I also didn’t want to spend that time administering my practice (which had become an overwhelming part of my studio life instead of making things). I wanted to immerse myself in an imaginative journey and here I have found the most authentic voice to make work from, so here I have stayed. Instagram has certainly become an extension of my work that hopefully brings a wider audience on the intimate and real journey of success and failures in my making. This is a living and breathing part of my practice that has different rhythms, and slowly things are opening up again for me, allowing other forms and materials to enter my making world which is a joy to share. It’s part of my generosity of spirit but also acts as a maker’s diary; I often look back at videos to remember how I did something. It’s a visual log book essential to any artist but especially a ceramicist who needs to keep a log of the experiments one does to remember the right settings on the kiln to achieve the perfect finish in the work. Well-honed skills developed for years are often logged in secrecy, instead I log them on social media.

Serena Korda, screen shot from Serena's Instagram feed showing work in progress in the studio, 08.06.12.

Archive

Looking through your website I was struck by the sheer amount of work you have made. There’s enough for a retrospective already! You have undertaken many site or subject specific projects and each one must have taken so much research, administration, making, directing, and documenting! How did you acquire all the skills needed to realise and manage these projects (for example W.A.M.A, 2012) and how did you avoid burning out?

Well, its strange to think that you have made a vast amount of work. I just make because it is integral to my happiness. I have been making works since 2004, projects that I deem as significant and part of my career - that’s almost 20 years of making right there. I always feel like I am learning and that in order for the art to have elements of risk, excitement and stay fresh there has to be an element of learning built into the work. My partner sees it another way; he says I enjoy building stress into my work, but hey, who knows, he may be right! There is definitely a point of collapse, worshipping at a temple to hysteria (as another friend once put it) pushing myself and my skill set to the brink. I learn on the job and then take this skill set and move it up a notch based on what I have learnt each time.

Serena Korda, 'W.A.M.A', 2012, public art commission and performance.

My work early on was fuelled by collaborations, involving the public, dancers and then musicians, learning how to bring the best out in others and manage large budgets and large groups of people. It was always exciting and somewhat precarious working with so many unknown elements but I loved the uncertainty of this side of my work. In many ways my focusing in on ceramics over the last few years certainly reflects that desire to add stress in my working experience - always living on the edge of whether the sculpture will make it through the process. Involving myself in complex rituals which is almost like brewing a fine wine. I don’t know if I do avoid burn out. I think I certainly experience a sense of loss at the end of every project and this earlier part of my work was hugely project driven. Things would not often carry over into the next piece of work and so, this enormous effort to gather people and information felt lost. I think this is where the pandemic and motherhood came in and nurtured a different side of my practice that I had been hankering after, one that was self-generative, a studio-led practice that was living and breathing and could keep growing. It means I don’t feel like I’m starting from ground zero each time and it definitely feels more nurturing to my sensibilities as an artist.

Serena Korda, 'And She Cried Me a River', 2021, documentation of the work being assembled by the artist.

Participation

Jenny Brownrigg, Exhibitions Director at GSA during your exhibition ‘Hold Fast, Stand Sure, I Scream a Revolution’ says ‘participation is part of her work, Serena directly works with people from the local communities’. Do you think post-pandemic funding cuts have altered the way artists make participatory works? Despite your shift towards a studio-based practice could participation filter back into your work in the future?

I definitely made a concerted effort to move away from participatory works. I think inherently what Jenny is referencing is an interest in communities, how group dynamics evolve and the agency of collaboration that drove much of my participatory actions. These sensibilities are intrinsic to my approach and not just something to add on as part of a funding application. I did feel people had started to define my work through community and I want to move away from this pigeon holing. I have never worked with a group of people just for the sake of a commission, I always make it clear to commissioners that my approach to participation is that the work dictates to me who I need to work with, be it a male voice choir, a group of children to be small wizened old men from Lancashire folklore or a call for people who own black cats to audition them for the starring role in my next film. That is my approach to participation. After the pandemic I found that people were wanting to work with communities for all the wrong reasons, their approach was skewed and to be quite honest it gave me the ‘ick’ so I just carried on doing my own thing until the right opportunity came along to work in this way again, which is with a new body of work I am currently making around fertility rights and menopausal women. This will be shown in a solo exhibition opening next year at East Quay in Watchet, Somerset.

Serena Korda, 'Hold Fast, Stand Sure, I scream a revolution', 2016, sound sculpture created for Reid Gallery and Comar as part of Glasgow International.

The Jug choir

The making of props and costumes runs throughout your practice, often in conjunction with choreography, music, and film. In The Jug Choir (2016) the objects you made seem to shift into focus, taking centre stage. Was The Jug Choir a pivotal moment in redefining your practice?

I don’t know if it was so much redefining my practice but as an artist I am so interested in growing through my work, that each project feels like a leaf unfurling, the world I am building becoming a little bit bigger. The Jug Choir was as much a discovery of my love of ceramics as it was about finding how I could use sound as a material whilst building confidence in how I used these two materials together. Again, through making this work the fact the objects needed to be sung into became apparent as I loved the way the sound bounced around them and into my studio. I knew I wanted people to sing into them. It was symbiotic and a lot of amazing things fell into place because the objects were setting the stage and guiding me in what needed to happen with them. It was also a work embedded in ritual, war, a history of violence towards women and about spell making and what that meant to us in today’s political climate. This is still very relevant to the moment we are living in as this work has been curated into many recent exhibitions; most notably A Matter of Life and Death, Thomas Dane Naples (curated by Jenni Lomax); The Horror Show!, Somerset House (curated by Iain Forsyth and Jane Pollard) and upcoming, I Put a Spell on You: New Magic and Mysticism at The Art Exchange, Essex University Art Gallery (curated by Jessica Tywman).

Serena Korda, 'The Jug Choir', 2016, installation and performance.

I always felt the importance of the way these sculptures had transcended their role in a performance; they had appropriated a wealth of history and lived such an experience of being sung into by so many people that they now really did have a life of their own. Jenni Lomax, my eternal art mother and the most wonderful mentor, had the foresight to curate the jugs into her 2023 exhibition, A Matter of Life and Death at Thomas Dane Gallery Naples. They were shown alongside a newer work 'And She Cried me a River' that was later shown as part of Strange Clay at the Hayward. This was the first time the jugs were shown without activating them; Jenni didn’t ask for a performance, I had also performed enough with the Jugs. I was interested in how Jenni’s curatorial genius could reframe these objects with their history of performance. It was amazing to experience these objects moving beyond their performative incarnation, but with that story adding provenance to their existence: People’s first point of contact to these works being their strange mix of beauty and the grotesque. I think this is the best kind of sculpture or artwork full stop: It draws you in because it is visually arresting but then its story unfolds and holds you there with it immersed in its world, in its universe.

A Matter of Life and Death, 2023, Thomas Dane Gallery Naples, curated by Jenni Lomax, installation view. Photo credit: Roberto Salomone.

I love world building. I love using this terminology to define my making process and over the last three years this world building has become a deep dive into the collective unconscious, into unbridled imagination! Not only this, but in making this work it was the first time I had used clay and taken it through the firing process. It was my love affair with ceramics that started but also my own growth in believing in myself to use sound as a material (as I am not a trained musician). When performed, this work wasn’t about making music it was about making noise and a loss of self and ego in the collective act of spellmaking. It was the first work that highlighted the beauty but also brutality of humanity and the beginning of the way I like to view my approach to making: which is the ‘weaponisiation of craft’. It was also me being very open about exploring ritual, witches and what that meant as a history of female genocide.

Serena Korda, 'Circus Witch', 2023, glazed stoneware, 24 K gold lustre, steel, wood. Photo 'Ben Deakin', ©Serena Korda. Courtesy Cooke Latham Gallery.

Invented Folk

Folk aesthetics are apparent across your work and you mention ‘I had staged several invented folk dances that were concerned with revealing abandoned histories’. What first drew you to folk dance as a medium and why was it important for you to subvert or expand existing histories or rituals?

There is something inherent in the folk dance that is not about being an expert, it’s something that anyone can perform. I like the fact it is handed down over generations but what I also love about folk is that many of these dances or songs aren’t as ancient as you would think and that all traditions are invented, so why not invent your own? Folk is inherently for the people and of the people, it is about community and inherently democratising a non-hierarchical route to performance. It plays out storytelling and has deep rooted connections to pagan rites and rituals. I have never aligned myself with any one organised religion but have deep interests in the feisty nature of paganism and its connections to the natural rhythms of life and death cycles and connections to the earth. Paganism, witchery, wiccan, are all about delving into the powers of the divine feminine and the more I can get of that, the better. I don’t define myself as a witch as I have a problem declaring myself as anything in particular but I identify with many aspects of this belief system. I think more than anything ‘folk’ is about opening people up and democratising not alienating anyone from casting their own spells or making their own rituals. I guess folk dance is about energy, unbridled energy, something rising up in the exponent that is attempting to connect it with spirits, ancestors and magic, and that is why folk dance and music from these rituals became so important to the works. I was brought up with the Jewish faith, I am not a practising Jew but again there are elements of the cultural aspect of this religion that I love and that are integral to who I am as a human.

Serena Korda, 'Decosa Tradition', 2010, documentation of performance.

Old Men's Flesh

Its apparent that you’ve been interested in the intermingling of gender, power, culture and myth for a long time, from Old Men’s Flesh (2004) right up to The Maidens (2023). Recently these themes have emerged in the use of Greek myths to revisit entrenched representations of women. What drew you to these literary sources of inspiration and what do you think we can take from these ancient stories as a contemporary society?

Greek myths are the stories I grew up with as a kid. Later you begin to understand that there are ultimately only 7 stories in the world that are retold across cultures and it feels like our understanding of heroes and heroines and the acts they perform have become entrenched, archetypal, symbolic and unquestioned. Women’s stories, or the lack of them, have been present in the work for many years, but their retelling became more urgent after having my daughter Yuffie. I started to question how I would continue the legacy of these entrenched tales. Did I really need to reinforce the idea of a knight in shining armour, did I need to paint women with power are monsters? So much of my work that is world building around an invented giantess has been about challenging the representation of these archetypal women. Through this approach I found many feminist retellings of women in myth, most notably The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood, which takes Penelope as the central character and gives voice to the otherwise silenced Maidens. I became interested in my giantess having her own entourage of Maidens helping her navigate and negotiate certain situations and so ‘The Maidens’ was born. As I said each artwork is in conversation with the next, generating its own narratives and its own mythology. The work has started to tell me which direction I need to go in and, ultimately, it’s a conversation between me and these invented narratives/characters.

Serena Korda, 'I Just Can't Get You Out of my Head', 2022/23, glazed Stoneware, imitation gold leaf and varnish. Stand: Polished steel, foam and MDF, 33 x 34 x 20 cm. Image courtesy of Cooke Latham Gallery.

The Maidens is not an illustration of Penelope and none of the works I have made in this series with the giantess are illustrations of these well-known myths. Instead, these entrenched stories are launch pads for an imaginative journey into an immersive world that allows us to re-examine our place in the here and now. These stories still have relevance - they are current. Look at Philomelia being silenced by having her tongue cut out after she was raped and finding a way to retell her story through the craft of tapestry. How does her story not reflect the silencing of women to the present day, being highlighted by actions like the #MeToo movement.

I also discovered the writing of folklorist Maria Tatar who speaks so eloquently in her rebuttle to Joseph Campbell’s text on Greek myth ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’. Her book ‘The Heroine with 1001 Faces’ exposes how if the women in these stories were not goddesses or monsters they had no agency. The only way that ordinary women could exert their power was through craft, hence her terminology of the weaponisation of craft. This concept resonated with me and felt like the perfect definition of what I had been doing for many years in the craft techniques that I had been adopting.

Serena Korda, 'Telling a Tale', 2022/23, glazed stoneware, imitation gold leaf and varnish each: 35 x 13 x 13 cm. Courtesy of Cooke Latham Gallery.

Tarantella

I loved watching your film, The Transmitters and felt that it coherently binds the defining features of your practice into one medium, in much the same way as your current ceramic work does. Can you take me through how you developed this piece in terms of working with musicians, dancers and camera? Are there any parallels with the way you work with clay?

I have a real fondness for the Transmitters so thank you so much for highlighting it and reminding me of this work that is dear to my heart. I had been making a lot of folk dances and rituals as you have noted. These projects had been bound to specific communities and places and I think the Transmitters really came from a desire to delve into my imagined world. In the early days of making participatory works I sometimes found it difficult to move away from the reality of place and then portals, voids and ‘thin places’ became a way to bring out the extraordinary in locations, finding ways to invite communities into my imagined worlds. So, the Transmitters was a reaction to wanting to make an imagined space but one that nodded to the communities and subcultures that had been fuelling my interest to make art in the first place. I think this one pushed into the realms of John Wyndham fantasy whilst thinking through relationships to community, addiction, ritual and femininity; these elements all coagulating in an uncanny ritual performed in an undefined yet familiar English village hall. The Transmitters came out of a period of working with a series of dancers and musicians who became close friends over a series of projects. I was also lucky enough to work with an amazing director of photography Belinda Parsons and close friends Rosie Heafford, Florence Peake, Julia Pond, Daniel O’Sullivan and Alexander D Tucker. Again, film made a performative action have the ability to move beyond the ephemeral.

Serena Korda, 'The Transmitters', 2013, video with sound, 12m 47s, video still.

I was fascinated by the relationship between actions dismissed as female hysteria and what was actually a type of freedom of expression in public. Young women defying the more austere conventions of the time period (the early 60’s) and seeing a weird eclipse just on the cusp of the free love movement that was about the rise of the teenager. All this cemented by the beats and rhythms of Rock and Roll, music driving girls crazy, allowing them to express an otherwise suppressed sexual desire.

Music has always been important to me and Daniel O’Sullivan was my flat mate at the time and a multidisciplinary musician, so I was surrounded by music making and witnessing his creative processes. Music felt intrinsic to my vision, especially as ecstatic dance practices were at the heart of it, and so the beat was the driving force, the energy, the heartbeat of the work. I met Alexander D. Tucker through Daniel and loved their Psychedelic Folk Pop duo, Grumbling Fur. I was in the house when they were developing and recording their first album and so my old-fashioned whistling kettle and my bike bell feature in the opening track. They became like brothers and so it was obvious to ask them to collaborate on the music and star as these seedy male pop stars inducing reactions in the female teen fans.

As I was making the work I was looking at ecstatic dance traditions and came across the southern Italian folk dance the Tarantella in which a young woman is sent into a frenzy of ecstatic dance to cure her from a supposed venomous spider’s bite. Local musicians would come to her and play music until she dances to a point of exhaustion having exuded the venom from her body. But she would never be fully cured and would have to perform the dance every year. What I later learned about this very male dominated society in Southern Italy is that this is a rite of passage for many of the women and their one moment to take centre stage and perform this coming of age. It is also supposed to be a safe space where women experiencing trauma, loveless marriages, and abusive relationships can cut loose and find real release in the frenzy of the dance and the catharsis of screaming and crying. Amelia Soth writes about the Tarantella on the Wellcome Collection website.

Serena Korda,'The Transmitters', 2013, video with sound, 12m 47s.

I remember trawling the streets of North London where I grew up, with my mum trying to find the right place to film but also a place that had two full days of availability. Very quickly I realised that these spaces I had grown up in learning ballet and tap were fundamental, well-loved and well used community hubs (so very difficult to get two full days free in them), again, the community and sense of democracy being underlying in the location of this film.

I had grown up watching musicals and this became fused with a newfound love of schlock horror films, horror B movies and cult classics like: Invasion of the Body Snatchers; Village of the Damned; The Wicker Man; Braindead; and Society.

All the movements were extracted and inspired by movements found in archival footage of Beatlesmania and I had a few days working with the group of dancers to develop the choreography for the film. We watched a load of archival footage and worked in collaboration to develop the different sections of the film, I was also interested in the symbolic power of the spider as well as its connection to the Tarantella and the idea that the ecstatic dance is induced by a spider’s bite, so the moves become more animalistic and transgressive as the film evolved. It was an amazing two days of filming, one of which involved a live tarantula coming on set with its ‘wrangler’, helping it perform to camera on the special cave set I had built it, making sure it didn’t escape!

Serena Korda, 'The Transmitters', 2013, video with sound, 12m 47s, video still.

Studio

What are you currently working on in the studio?

I am currently tackling my first Anatomical Venus, I have been drawn to them for many years now. I have also been shying away from representing the full female figure so directly in my work up until now but this is a full blown attack on centuries of the male gaze whilst questioning female representation in art and scientific history. The Anatomical Venus suggests this sexually heightened female body being pulled apart. I am interested in using her to reclaim female bodies of many different types questioning our perception of our own bodies as women. All of these women will be menopausal and post-menopausal, a massively underrepresented female figure in society. So, the work is also about considering another female archetype; the Crone, and reclaiming her from being written off and disregarded as she is no longer deemed “productive” but reimagining her as the wise, all seeing, all knowing, wild woman that she is.

I am reading Clarissa Pinkola Estés' ‘Women Who Run with the Wolves' which is really resonating with a lot of ideas that I am thinking about. Alongside all of this I am also dealing with the real-life grief of losing my mother earlier this year. My work is not overtly autobiographical but it is always a reflection of my lived experience and a cathartic response to it. As well as this there are a lot of apples being cast whilst I think about the fertility rite that is Wassailing. This is performed all over Somerset and other cider making regions and is about warding off evil and bringing in good spirits to make for a good harvest. There is a new sound work brewing and I am very excited to be working in the amazing Claire Partington's studio over the next few weeks to fire my first figure. Fingers crossed I have to transport a leather hard 97 cm meter tall Crone and then perform the hollowing out process which I have never done before! All exciting and life affirming stuff.

Serena Korda, work in progress in the studio, 2023.

Friends

Which artists’ works (historical or contemporary) are important to you at the moment?

Michelle Williams Gamaker’s Fictional revenge and fictional healing. I have known Michelle since meeting her at Middx Uni to do our art foundation. She is truly inspiring and her vision is so clear and I love her support, generosity and talent.

Eleanor Pearce - I was at college with Eleanor, and myself, Michelle Williams Gammaker and Eleanor all collaborated as Where are the Girls for the first year of our degree. It was amazing, galvanising and empowering and we are all still close friends today. Eleanor is an incredible draughtswoman, artist and community arts organiser.

Phoebe Cummings - I think Phoebe’s work is utterly beautiful and breath-taking but also so conceptually rigorous. I was so pleased to show alongside her in A Matter of Life and Death. She is such a risk taker and the performative use of clay in her work is unsurpassed.

Historical interest in Reliquary Busts and mimicry generally in New York Met Cloisters.

Clemente Susini’s Anatomical Venus 1780-182.

All the different sculptors in the Sansevero chapel, Naples most notably Francesco Queirolo, Giuseppe Sanmartino.

Serena Korda, installation with Cooke Latham Gallery at the Armory Art Fair in New York, 2023. Photo by Mikhail Mishin, ©Serena Korda. Courtesy Cooke Latham Gallery.

Shahpour Pouyan - who I was lucky to meet through Strange Clay. His precision in clay and again beautiful yet conceptually and politically powerful works are inspiring.

Florence Peake - who is so generous and vital fusing worlds of dance, painting, ceramics and somatic movement. Am so very honoured to have met her through the making of my work and become close friends after collaborating on several dance inspired works.

My dear friend Flora Parrott who is a meticulous and rigorous sculptor/installation artist, making astoundingly beguiling and beautiful installations and works around darkness and what that opens up psychologically.

Tom Woolner - love his studio practice and the anarchy and humour of his performance work.

Frankie Gallagher - an amazing maker, curator, artist and technician. She worked with me on my Baltic show and performed as one of the arms in my giant beast at Camden Arts Centre. I love our chats and find her vision and insight inspiring.

Claire Partington is very inspiring. She makes the most beautiful depictions of women from mythology and merges historical references with popular culture sublimely. She's also lovely as she's let me invade her studio to finish off my Crone who is too big for my kiln!