Shaan Bevan is based in the Montagne Noire, Southern France. Bevan works primarily with painting, drawing, writing and installation as a method of processing her personal history with disease and chronic illness, while exploring expansive modes of healing. Across her work, she explores how bodily phenomenologies are embedded within a network of Earth systems, complex ecologies and material histories, with a goal of reorienting from a reductive empirical understanding of the material self.

Prelude

Shaan, I first met you at the Slade a couple of weeks before your MA show. As you already had a rigorous plan in place for your installation, we talked more widely about the experiences and research fueling your practice. Your exploration of materials, medicine, and the body is so rich I wanted to continue the conversation. Before we begin, how did the show go for you? Were you happy with the way your installation came together, and the curatorial conversation with Cheuk Yiu Lo’s Sculptures?

Thank you, Fay. I loved the conversation we had, it’s not everyday when ideas weave together like that - such a pleasure. I’m really proud of the piece and was humbled by the curation, to show alongside Cheuk Yiu Lo’s brilliant work in that round room was a great privilege.

By the time I installed the work I was so burnt out. I’d been in my energy overdraft for about 11 months leading up to that show and landed myself with every red-flag health symptom and flare up. It was blissful to see it installed — it was a huge confirmation of effort to feel love and pride for the outcome. It was surreal to experience the feedback from a much bigger audience than I’d ever encountered before. But I’m now refocusing my attention to ways of structuring a work balance that is much healthier and more sustainable for me.

Shaan Bevan, drawing development in the studio, 2023.

Art and Medicine

The semicircular space you exhibited in reminds me of the architecture of historical operating theatres - where (in front of an audience) the body becomes object, science, knowledge. The surgical procedure is part spectacle, part pedagogy. Did the wider context of the Slade (sitting alongside UCH), and the connections between life drawing, anatomy, and medicine, influence your decision to study there? Or were you drawn to the Slade for its Painting specific MA Course?

I had a close friend undergoing cancer treatment at UCH while I was applying to the Slade, and I’d spend time in the chemo wards keeping him company while I was thinking about studying there. It was an experience of being on the other end of research being conducted at UCL, and a personal confrontation with our tender dependence on the life saving technology that can be progressed in university hospitals like UCH. I wanted my friend to get better so badly, and held a lot of hope in his treatment as he underwent every experimental clinical trial and new immunotherapy appropriate to his disease.

Endless hours spent in chemo wards with him and during my own cancer treatment, has brought my attention to something gravely missing from the heart of these clinical spaces. There is a chilling psycho-spiritual emptiness related to how medicine is practiced, that makes me wonder what questions regarding good medical care an artist, a poet, or a spiritual practitioner might be more equipped to answer than scientific methodologies. How can we better nurture the psycho-spiritual ruptures that happen when bodies undergo complicated processes of illness, trauma, disease, and treatment?

Shaan Bevan, ‘Exhalation, after the storm’, 2023, ceramic bowls, wire rope hanging system, ultrasonic misters, seawater, geosmin, mitti attar, patchouli, ambergris. Each bowl is 30cm x 30cm x 18cm. Photography studio Adamson.

There are a lot of rumours about the history of that semicircular room in the Slade where I showed my work, and my understanding is that it was an operating theatre at some point in the building’s history, or at least part of the medical campus. That played on my mind a lot during the show. I’m interested in the subject position of the patient undergoing the uncanny process of becoming a data body within the clinic.

During my own diagnosis, I rigorously researched my disease, and began understanding myself in terms of blood counts, medical imaging, and biopsies, and learned to empirically interpret what I was sensing internally so I could communicate my experience with my doctors. Communicating in precise observational terms was almost exclusive in how I could relate with my medical team. There were a few nurses who managed to pry a few sacred minutes from their their relentless, underpaid working days for more personal and emotional discussions to support my terrifying experience, but this wasn’t often the case.

Shaan Bevan, Positron Emission Tomography (PET) scan of artist’s upper body, 2018.

I felt a wall between that rigid, reductive, clinical world that I was existing in, and my internal universe - a world of felt experience exiled as unhelpful in saving your life, in the Western medical context. There was a simultaneous divide between my body and the natural world, since the clinic itself represents a controlled sanitised environment. For example, in the hospital, a cancer patient is not allowed to receive flowers from loved ones because as the flowers inevitably break down, they can harbour bacteria harmful to the patient whose immune system has been obliterated by the chemotherapy. Within the necessary limitations, I wonder if Western medicine could ever find a way to hold clinical space for the rich poetic fabric that is being a body, the emotional worlds, huge shifts and floods of the nervous system, memories, terror, ecstasy, visions and somatic experiences that are conjured while undergoing medical interventions and the endless hours of waiting in dead boxes that smell like chemicals. My deep longing to express and communicate on this more poetic emotional and erotic level within a system of care is why I started making art.

An art school inhabiting an old medical department felt symbolic and haunted, representing a tension between worlds. The meeting of the poetic and empirical were embedded in the bones of that room at the Slade, as were complicated histories of the ways medical research has dehumanised its subjects in the quest for knowledge and power. I guess if anything, exhibiting in that room felt appropriate and materially charged in terms of the questions I was asking.

Shaan Bevan, 'Adriamycin - femmes, farmers, pharma', 2022, ruby, urine, mercury sulfide, volcanic ash, iron oxide, antidepressants, seawater, pencil, gum arabic, honey, 234.5 x 162.5 cm, Zaza' gallery, Milan.

Below the Surface

In ‘The Origin of Windows and Fevers’ there are many materials and subtexts that eloquently co-exist: Earthy scents; rigid medical apparatus; sublime turquoise seascapes; and descriptive, sequential titles. Where is this system of describing and measuring the sea’s movement from and why was it such a compelling a metaphor for you?

The drawings were in reference to the Beaufort wind force scale — a 19th century empirical scale used originally by the British Navy, numerically categorising wind speed based on the observable conditions on sea and land. It ranges from zero, where calm conditions are described quite beautifully as:

sea like a mirror, smoke rises vertically

Through to twelve, describing hurricane force winds:

air filled with foam and spray

the sea is completely white

visibility is seriously affected;

devastation

I stumbled on this scale while researching weather systems, and was struck by the confrontation between the empirical and the poetic in the descriptions. I found it really beautiful and absurd.

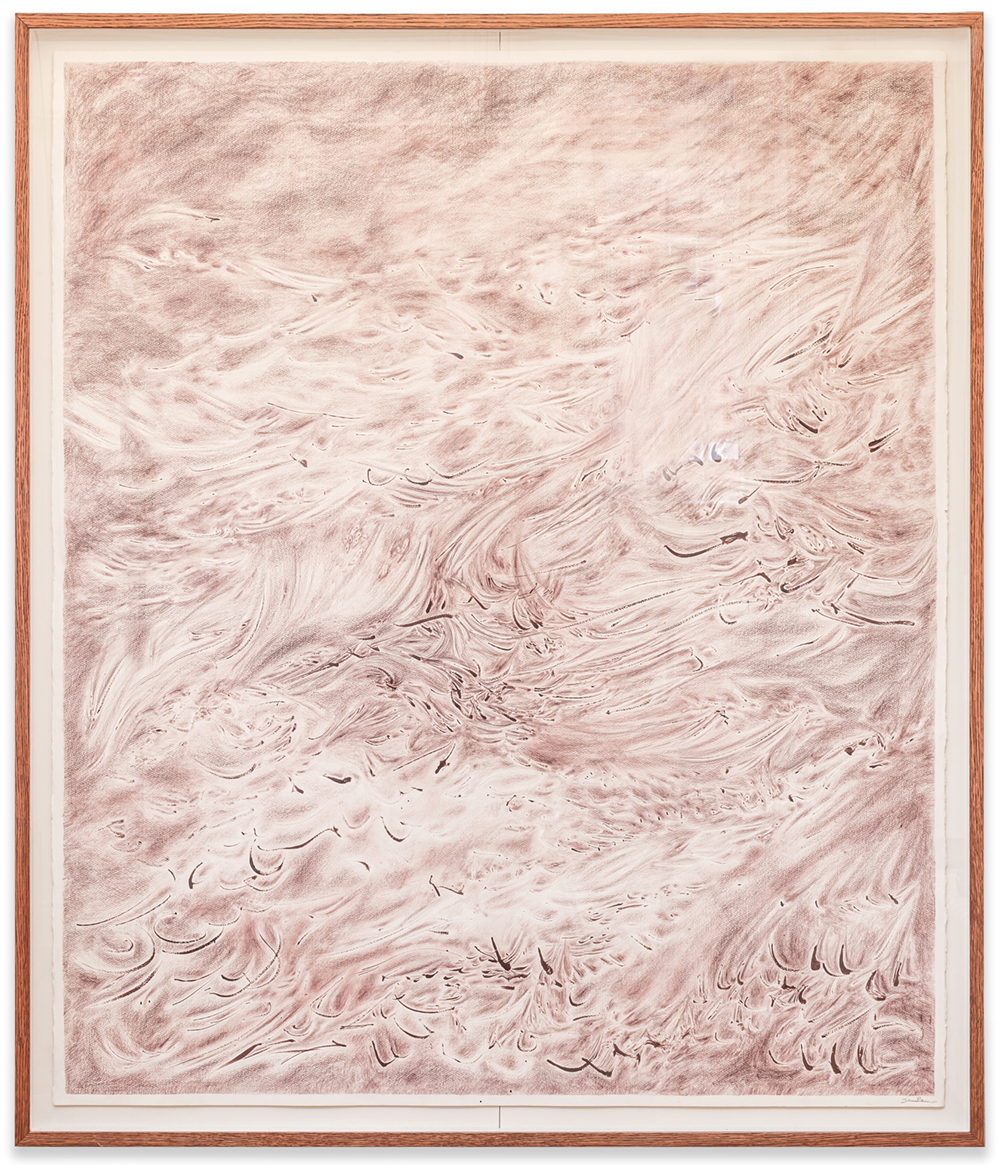

Shaan Bevan, ‘8 - Moderately high waves of greater length, crests break into spin-drift, foam is blown in well-marked streaks along the direction of the wind, generally impedes progress’, 2023, pencil on paper, oak, glass, aluminum tube clamp system, wooden board, 170.8 x 127.2 cm. Photography studio Adamson.

For that installation, I imagined a patient in the hospital bed. While tethered to a medicated infusion loop, she is simultaneously enclosed in a sanitised environment, which is closely controlled to keep all unwanted Earthly biologics out. I imagine it as an attempt at a closed system within a closed system. I referenced this enclosure with the formation of drawings installed on industrial metal stands alluding to medical partition screens, and the picture frames themselves represented a second enclosure, isolating each drawing into environmentally controlled conditions based on museum conservation practices. The patient in my vision is nonetheless filled with emotional storm systems and primordial urges to be emerged fully back into the violent and nourishing cycles of the Earth. It was a poetic acknowledgment that the storms at sea are felt inside the body —they are environmental as much as they are the material of the body itself in relation to deep time and the evolution of life on Earth. It also acknowledges my own personal struggle between poetry and empiricism, where in order to make sense of my unpredictable internal weather and the progression of my disease, I desperately try to place all of that sensory feeling back into a scale of defined and categorised data, which is as helpful as it is totally absurd. As impossible as dividing the relationships between seawater and air into 13 cleanly partitioned categories, each drawing represents the absurdity of a tourniqueted category of felt experience.

Shaan Bevan, detail image of ‘8 - Moderately high waves of greater length, crests break into spin-drift, foam is blown in well- marked streaks along the direction of the wind, generally impedes progress', 2023, pencil on paper, oak, glass, aluminum tube clamp system, wooden board, 170.8 x 127.2 cm. Photography studio Adamson.

I wanted the installation to feel enveloping, and to affect the nervous system akin to how it feels to sit in front of an expansive body of water. Finding meditative orientation within the body can be scary when the body itself is a source of fear and pain. In my case, I found that the sea can provide a useful external orientation of meditative grounding that connects the body to a greater whole, an ecology of and outside the self.

The curved walls allowed the drawing installation to hug beyond the periphery, and I was surprised to see the blue colour from the drawings diffused through the natural light of the room, affecting a parasympathetic quality that I can’t quite describe with words. I’m now curious about how light can inform vagal experiencing.

This desire to gently shift the nervous system is also why I chose to hang the ceramic bowls above the heads of the viewer. The bowls contained perfumed seawater, which was ultrasonically atomised into a gentle mist, filling the air of the room. I was hoping the audience’s experience with the odour would be felt before it was seen or understood materially. Our sense of smell is unique in that the olfactory membrane is the only place in the human body where the central nervous system comes in direct contact with the environment and its chemical constituents. Odour gets straight to our limbic lobe - the seat of our emotions.

Shaan Bevan, detail image ‘Exhalation, after the storm’, 2023, ceramic bowls, wire rope hanging system, ultrasonic misters, seawater, geosmin, mitti attar, patchouli, ambergris. Bowl, 30cm x 30cm x 18cm.

The main ingredient of the perfume accord I designed for the show is called Geosmin. Geosmin is the molecule responsible for the Earthly smell of soil, and it is a common contaminant in municipal drinking water resulting in an ‘off’ taste, as it is a byproduct of many microorganisms, including almost every strain of the soil microbe streptomyces and several species of cyanobacteria. I adore the smell - it reminds me of childhood memories in Wales — of rain, moss, lichen and wet stone. I imagine it as an Earthly invasion of the clinic, getting straight into the bodies within the room. Geosmin also relates to my own experience in the infusion chair, because one of the most brutal chemotherapies I was treated with, Andriamyacin, is itself a derivative of the streptomyces peucetius microbe. Researching the origin story of Andriamyacin helped me acknowledge the ancient soil, harvested off the coast of the Adriatic Sea (as referenced in its name), that was molecularly infused into my body with warlike toxicity. These material poetics help me connect my medical experience to an important spiritual initiation. My body and the medicines I consume are materially Earth, and we are intimately interacting in our current forms while on a greater process of material transformation. To consume and to be consumed in endless cycles of life and death, we are all in a deep process of chemically rearranging back to soil, rock, weather, and sea.

Rupture

When you write about being an oncology patient there is a sense that illness precipitated a radical change in the way you conceived of yourself and the world; an irreversible ontological shift, where you describe yourself as becoming ‘an open system’. Can you tell me a little more about this shift? Was becoming an artist a way of processing this perceptual transformation?

Of course as bodies, we are all open systems. We eat, drink, sense the world, we take in particles as we breathe the air, our nervous system sends signals to our muscles to tense up when we sense danger, a gentle tone of voice can encourage a positive shift in our digestive system, a ray of sunlight is metabolised chemically in our cells — we are beautifully permeable beings.

What I was referencing when I wrote about becoming an open system was more psychological than physical, describing a period of rapid breakdown in my ability to regulate my emotions. In my life before my disease, I experienced the world with a conditioned numbness that is symptomatic of our late capitalist culture. Subconsciously I prided myself on my emotional and physical endurance for terrible conditions, abusive environments, and having few personal needs or limitations. My illness changed that without warning and suddenly in 2018 I might find myself in a terrified panic attack from a loud voice on the bus, or in disabling shutdown for days after an unremarkable argument. The endurance I depended on for so long had vanished, it was like the floodgates were opened to every repressed fear of my life, and my inner demons were everywhere I looked. Being diagnosed with CPTSD was really helpful with understanding what was happening in me, but I understand it on lots of other levels outside of the DSM-5 too.

Shaan Bevan, '8 - Gale', 2023, dracaena cinnabari, ethanol, pencil on paper, 159 x 143 cm. Photography studio Adamson

Before my diagnosis, I knew I was sick but it never occurred to me that my nagging cough and chronic fatigue could be caused by a large network of malignant tumours in my neck and chest – it was a complete shock. I remember leaving Saint Bartholomew’s Hospital for the first time, feeling like I was in a dream — I felt atmospheric and unreal. The new world felt wobbly, fluid and unfamiliar and that feeling lasted for a long time, in fact it never fully left me. I understand this now as a dissociative limbic response, but at the time I just understood it poetically, I still believe the poetic understanding gets closer to the truth. The emotional waves and disorientating currents were profound, both due to the process of grieving the loss of my health, as well as the fear and uncertainty of what was happening on a cellular level inside of my body.

Environmentally I lived on a street with a lot of violence outside of my front door. I witnessed a stabbing the night before my second chemo and my building was being broken into regularly. I would beg my landlord to fix the broken lock on our building but somehow it wasn’t his legal obligation so he refused. My flat was robbed while I was in the hospital — I came home groggy and nauseous to my front door ripped off the frame, and all of my stuff broken on the floor like a tornado had passed through.

My family lives in the United States and because the country refuses to provide universal health care (while paying for the most well funded military and police force in the world), it was not possible to have my treatment close to family. I had a limited social support network in the UK and I was conditionally terrified to ask for help without knowing it. The emotional and physical support I needed wasn’t easily accessible, and I didn’t realise how dangerous that was at the time.

Shaan Bevan, ‘Anistemi - carcinogenesis’, 2019, ash, walnut ink, iron gall ink on paper, 112 x 76 cm.

After years of processing, I’m clearer on the greater politics underpinning my ultimate rupture. The UK housing crisis, American healthcare politics, neoliberal austerity policies exacerbated under 12 years of Tory governance in the UK, a lack of workplace regulations, and a good dose of my own internalised ableism. It’s not possible to know for sure the truth behind my own carcinogenesis, but any cancer patient will theorise nonetheless. I’m convinced mine was connected to an extremely toxic culture of work within the fashion industry in London. Both in my undergrad and first industry job, working all night without sleep, abusive relational behaviour and unrealistic expectations of productivity and perfectionism was completely normalised by tutors, brand managers, funding organisations, peers — everyone. The fashion industry in the UK doesn’t have a union and the lack of work regulations is exploitative and dangerous. My health started noticeably degrading while I was working as studio / production manager for a young fashion brand with notoriously bad working practice — I had my first flare up of guttate psoriasis which is an auto-immune skin disorder during a particularly stressful season. Auto-immune disorders are chronic conditions that are often triggered by long-term allostatic loads caused by biological, psychological and/or social stressors. I was diagnosed with cancer of my lymphatic system a year and a half later.

Throughout my recovery, the process of making art was absolutely fundamental in finding stable ground again and underpins my entire healing journey to this day. In the early days, it facilitated a safe and nourishing activity that could get me out of the sick bed. The seas I would draw were both metaphorically and somatically therapeutic. I think what was happening without knowing it at the start, was that I was forging a conscious connection to an ecology bigger than myself, conjuring a route out of the claustrophobic confines of the domestic and clinical spaces I was inhabiting as a very sick person, into a world that expands beyond material boundaries into a nourishing connective cycling lifeforce, represented by the waters that support all life on this planet. I’ve been deepening my embodied understanding of that very real and ancient connection through the daily practice of making my watery artworks, through long devotional hours of drawing, through my engagement with the material world via the artworks they inspire, through constantly imagining my bodily experience as akin to fluid dynamics and ecological systems. I cannot separate my practice of making art from my practice of healing.

Becoming an open system was filled with deep challenges, and readjusting to this new bodily condition in a way that works best for me, with the goal of relating to the world in a way that prevents harm and encourages social and ecological nourishment is how I understand the concept of healing. Ruptures are as painful as they are necessary to enable growth, and they are integral to the human experience. Our culture cultivates so much unnecessary rupture while actively destabilising our systems of care. I am grateful to my own rupture for casting light on socio-political factors that inform so much unnecessary individual, ecological and collective trauma and I hope we can find our way back to better systems of care that are fundamentally embedded in the fabric of our social relationality with each other and the world.

Art or Alchemy

In your work I feel a tension between taking control of mark making and letting the alchemy make the aesthetic decisions. I’m thinking about you spraying misted seawater onto your Iron Paintings throughout the show ‘The flesh of the world crying out in a language of our own waste’, for example. Are you interested giving the chemicals you work with their own aesthetic autonomy, or do you tightly control the situation, like a scientist in a lab?

Definitely more the former but there’s always a push and pull, sometimes even a little war between my internal axis’ of control and surrender.

I began my material research with an interest in historic paint recipes and organic pigments. I felt more connected to the colours I was using if I knew their origin stories – how they were formed, where and how they were extracted from the Earth, how to process them into other forms, their possible applications, their material politics, cultural histories and mythologies.

Pigment production usually strives to achieve the most vibrant and uniform colour while maintaining chemical stability over time. This in part involves grinding a material to its smallest particle micron before losing valued properties, or dissolving the crushed material into a fluid and evaporating off the liquid into what’s called a lake pigment. The goal of paint has a lot to do with making the material particles themselves imperceptible — a flattening and homogenisation of material so that it can be understood as colour and image. I realised I was much more interested in the material constituents themselves, which shifted my focus away from traditional methods. I also felt that the erasure of materiality meant that there was little transparency around greater ecological and sociopolitical considerations.

Shaan Bevan, ‘Tremble wail for the whales’, 2022, oxidized iron and gum arabic on wood panel. Installation: seawater, plastic tank, misting system, laboratory clamps, wood, 19th century blown glass female bed pan, 249 x 174.5 cm. Image courtesy of Zaza ‘ gallery, Milan.

Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the concern for material stability within paint manufacture and conservation practice, and how these efforts align with my questions and values. If my practice questions states of stability and instability within systems and bodies, and how things move in and out of equilibrium - making art objects using materials with the core value of consistent stability over time feels out of alignment. Further, forcing an artwork to stay in its current material form indefinitely, requires a lot of energy and resources, and positions an artwork outside of the fundamental natural cycles of life and death. I’m not against preserving our cultural history, and I understand that in geological time our cultural artefacts will never escape their cycles through form, no matter how well preserved they are in our time. But I think there might be more value than we culturally appreciate in allowing some great art to rot, like fruit on a tree - just to challenge our worship of immortality and to say something honest about life. I’d love it if we thought more about our art in terms of good compost material. When it breaks down, will it poison or nourish the ground?

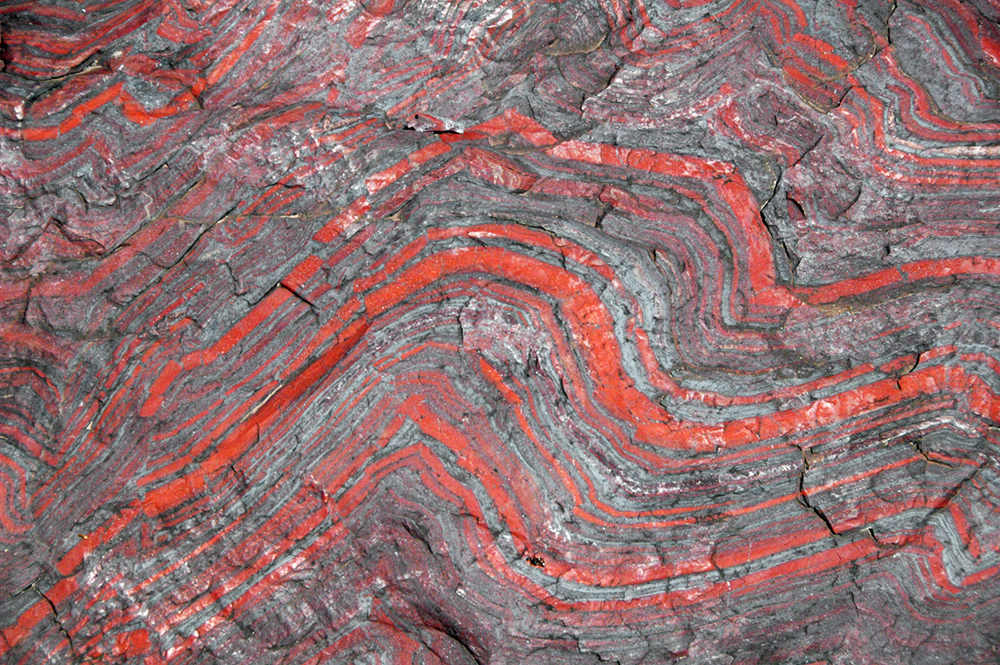

The iron paintings you mentioned are a meditation on material transformation itself. Iron + water forming ferric oxide (rust) is a highly visible and readily understood chemical reaction. We are constantly exposed to it when we see red tinged soils and rocks, rusty fences, the prehistoric red hematite cave paintings in the Grotte de Lascaux, and our own oxygenated blood. I like that it’s chemistry that everyone knows well.

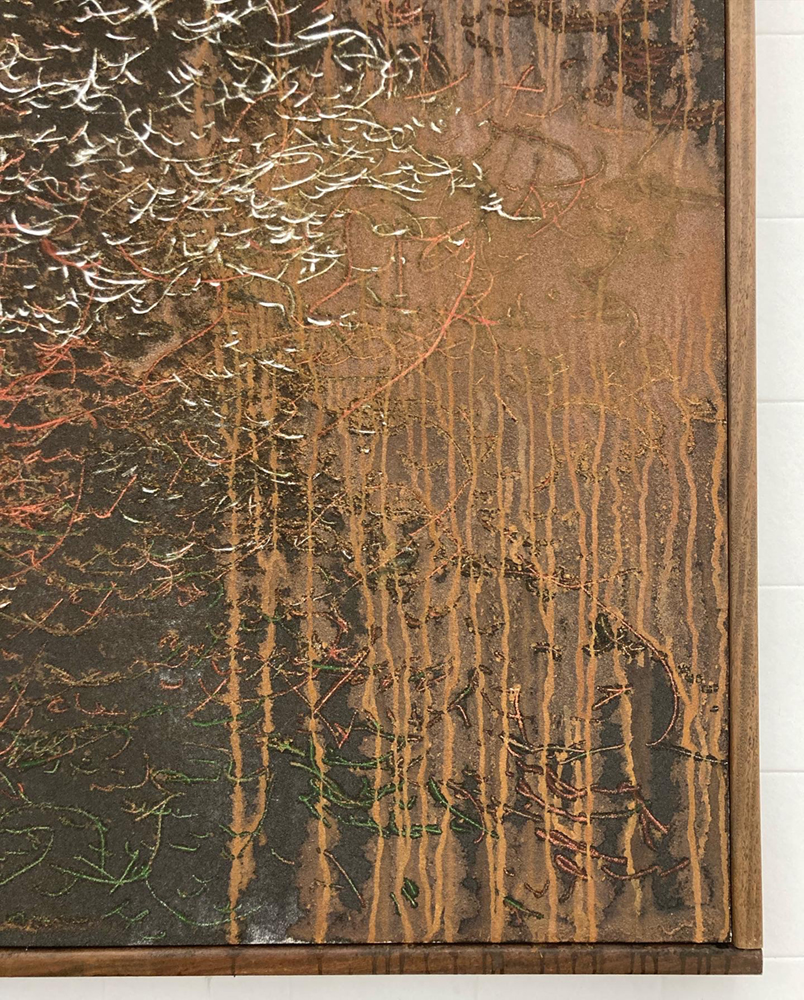

Shaan Bevan, Jwdqoehfqehfbiwej – Djfowejhfjkqhefkjejf – Nwoenfoewnknn, 2022, iron filings, mercury sulfide, aluminium, opal, chromium oxide, caput mortuum, volcanic ochre, Verona green ochre, ruby, stil de grain, Andalusian red ochre, green quartz, linseed oil, gum arabic, honey, 126.5 cm x 174.5 cm. Image courtesy of Zaza' gallery, Milan.

Transformations like trauma and disease are difficult to understand in a temporal sense. My cancer for example could be understood as beginning in 2016 when I started feeling sick, or 2018 when the malignant Reed-Sternberg cells were confirmed in my biopsies, and ending in 2019 when a PET scan confirmed my disease was in remission. But if you think expansively about it, the boundaries are so much blurrier.

Amongst other things, experiences in my childhood conditioned me towards perfectionism, which informed my willingness to be part of a labour culture that is exploitative. White- supremacist capitalist patriarchal cultural models encourage and feed on this kind of conditioning. How many generations ago did our relationship to the food cycle, labour practices and the extraction of resources change so much that our genetics were modified towards our current ever-increasing cancer rates. How does the damage of chemotherapy and the ongoing physiological stress from my ruptured mental health inform my ability to remain in remission? The ‘event’ blurs into a different temporality…

Those iron works directly referenced The Great Oxygenation Event, which is a geological event that occurred roughly 2.4 billion years ago. During the Paleoproterozoic period, the atmosphere was hot with carbon dioxide and nitrogen, and practically devoid of oxygen. Due to a lack of oxygen, terrestrial iron did not oxidise, and ferrous iron is water-soluble. This resulted in tons of iron being dissolved into the rivers and oceans. Cyanobacteria metabolically converted CO2 into Oxygen through photosynthesis, and every molecule of oxygen they produced was chemically absorbed into the sea. This process of oceanic oxygen absorption went on for hundreds of millions of years until seawater hit saturation point and all of the iron had transformed to ferric iron which is not water soluble, turning red and sinking to the bottom of the ocean. The primordial seas quite literally rusted, and this blurry, hundreds of millions of years long event allowed life to evolve onto land, and is connected to why we have salty red iron-rich fluid running through our veins.

Banded iron formation produced during The Great Oxygenation Event, James St. John, Jaspilite in the Precambrian of Michigan, USA. CC BY 2.0 creativecommons.org, via Wikimedia Commons.

I made the paintings by sieving iron powder onto a sticky wood panel that was covered with a tree resin otherwise known as gum arabic (traditional watercolour medium). I used the medium as a glue rather than a binder because I needed the iron particles to remain exposed to oxygen to encourage a chemical reaction. I engraved a drawing of the sea into the wet surface.

For the exhibition, I installed the paintings on the walls, framed by misting circuits. A pump circulated seawater from a tank onto the surface of the paintings. I knew it would rust but that’s about it, I wasn’t sure how long it would take or what it would look like in terms of mark making. The first time I ever sprayed the paintings was for a total of three minutes on timed cycles over the course of the opening.

The next morning, I was shocked to see that the paintings were already covered with very vivid orange streaks. The misting radius was not very big, so each misting head hit a concentrated area and dripped in rivulets down the surface of the painting. The transformation was much faster than I had anticipated, and the image it created reminded me of weeping tears or a deluge of rain over the surface of the sea. My intention was to use the idea of the Great Oxygenation Event to talk about the blurry, profoundly transformative experience of disease and trauma, and to also hold space for any transformative grief including the deep anthropomorphic transformation we are currently witnessing with climate breakdown, allowing a sort of symbolic witnessing to an event that’s temporality is so hard to imagine. Because my first experiment with this approach to painting happened during the exhibition itself, I got to be a viewer to the transformation and grief expressed by the painting. That was a really amazing experience.

Shaan Bevan, ‘Jwdqoehfqehfbiwej – Djfowejhfjkqhefkjejf – Nwoenfoewnknn', 2022, iron filings, mercury sulfide, aluminium, opal, chromium oxide, caput mortuum, volcanic ochre, Verona green ochre, ruby, stil de grain, Andalusian red ochre, green quartz, linseed oil, gum arabic, honey. Installation: seawater, plastic tank, misting system, laboratory clamps, wood, 19th century blown glass male bed pan, 126.5 cm x 174.5 cm. Image courtesy of Zaza' gallery, Milan.

Writing

I enjoyed reading your texts ‘This wound is a world, iridescent, shimmering: illness, art, integration & materiality’ and ‘Three Accords’. You are an incredible writer, bringing together personal experiences and a wealth of research across the arts and sciences. Do you have any plans or ambitions for future writing projects?

Aw thank you so much - yes I think the best thing that happened during my time at the Slade was finding my voice with writing. I never knew how useful a tool writing could be for me, it helps me make sense of things in a way that I haven’t found a vocabulary for in painting. I love that the artworks can be very visceral and poetic and undefined. Some of my drawings look like disembodied calligraphy, like marks that are trying to be words but sort of fall apart into feeling. I think I’ve entered a phase in my life that things are starting to crystallise in a way I’d like to express more directly through language. I also feel a political urgency has been growing in me for a long time that hasn’t found a home in the paintings. It’s not that I don’t believe the paintings are political - I know they are deeply political. But crystallising and clarifying a greater breadth of thoughts into language outside of them feels like the right outlet at this stage.

You are the first person who has invited me to write something publicly (thank you!) and I hope get a chance to write more this year. I’ve been collecting lots of research and doing some experimental things like transcribing active imagination that I engage with during IFS meditations for example. I have been dreaming up a novella that weaves theory, science, with very personal poetic and mystic experience, broken into chapters definite by the orders of wind in the Beaufort scale. I hope to use it as a supplementary text for an exhibition coming up this summer - if it’s done in time!

Shaan Bevan, markmaking in iron work in progress, 2022, iron filings, gum arabic, honey, on traditional gesso poplar panel. Image courtesy of the artist.

Future

What is your focus for the near future?What is your focus for the near future?

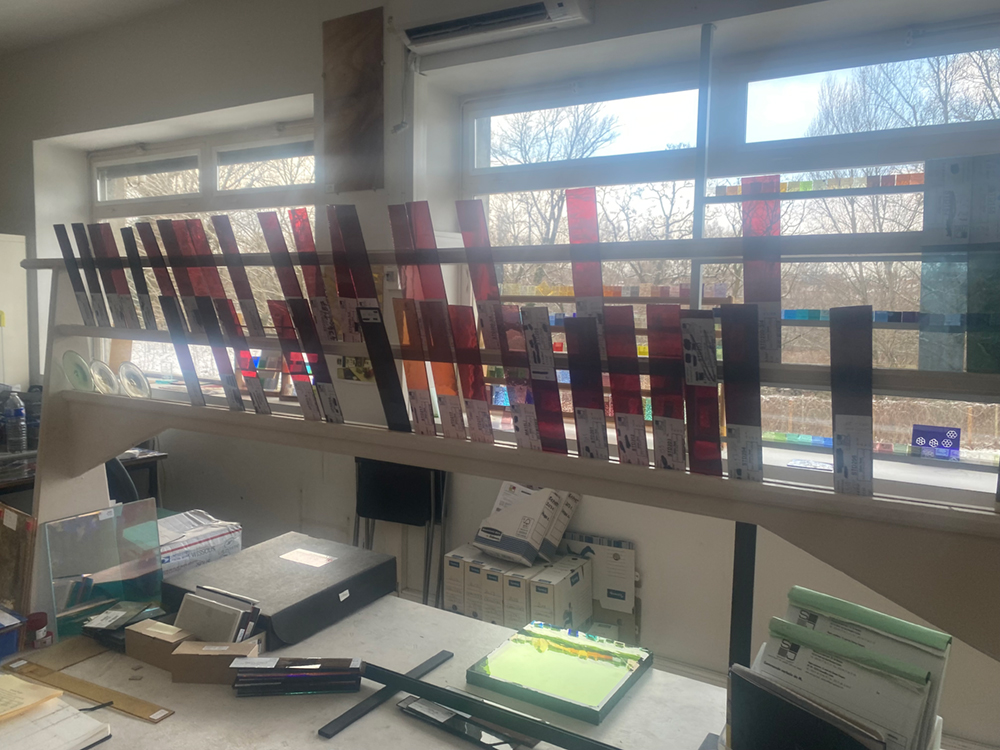

Right now I’m finishing up a new body of work for my first solo show in London, Inundation which is set to open in April at Des Bains. For this show, I’m exploring a relationship between the rhythm of flood waters in relation to the pulse of emotional experience and bodily somatics during events of rapid and widespread loss. In addition to my drawing practice, I’ve been working with hand blown coloured glass from Saint-Just, a glass factory in France which still produces sheet glass using historical methods. I visited the factory in January, and a whole world of poetry has been opening up as I begin working with the material that I can’t wait to explore more deeply.

Research documentation, glass samples - many shades of red, La Verrerie de Saint-Just, 2024. Image courtesy of artist.

After Slade I moved back to my home in the mountains of Southern France with my partner Owen Pratt, who is a musician and sound artist. It’s been amazing to settle back into working here. The mountain is endlessly inspiring, and I’m working to root my practice in the local ecology of this place. I’m also excited to work more closely with Owen, as our individual practices are growing in really harmonic ways through living here together. We have made a sound piece together for the Des Bains show that I cannot wait to share. We are eager to collaborate more in general, and are working towards a duo show that will open in London October 2024.