The mind circles back…

Hannah, the last time I saw you in real life it was 2008 whilst we were living in what you have described as ‘The Warehouse of Hell’ in North London. I remember you selling some belongings before leaving the country for Germany. You recently mentioned that your mind has been circling back to the work you made in 2009 when you ‘escaped’ London for Leipzig. Can you tell me about that work and which aspects of it are holding renewed significance for you?

God, that warehouse. I went to sleep each night not knowing if I would wake up alive in the morning. It didn’t help that my sleeping quarters were directly above a working kiln. I can’t remember if we spoke much about work there as usually we discussed things like the rampant fungi in the shower, but seeing your recent Instagram posts around dance and movement, I was invested in similar research then. I undertook Laban classes with Rosemary Brandt, to understand the body from the inside, as it were. I choreographed a kind of slumpy dance of women, set it to the Dirty Three and drew from a film we’d shot of it. The scattering of falling-down women formed the basis of some 2.5m x 1.2m canvases I painted in Leipzig, widescreen.

Other paintings were perceptual, around the recollection of colour, light and landscape – painting as a dream space. What one might call more abstract. I worked on them at the same time as painting imagined portraits, and pairs and groups of figures. Together, they formed a way of thinking that I termed an island space of the imagination, a mythic site upon which characters entered and departed, dragging the remnants of art history behind them.

I had a huge studio, a couple of floors below Neo Rauch’s. I would wake at 5am with the sunrise and the workmen carrying ladders and breakfast flasks over the rooftops. I love the work I made there. I know now I was setting out my various tempos as painter, the counterbalances that exist within this open narrative I’ve always worked with. It was the first and last chance I’ve had to work like that, to show the way I think and perceive from one canvas to one drawing to a set of words. I’m kind of sad about that. It’s difficult to express this interplay on a form like Instagram. But yes, I’m working with those tempos in the studio, and painting large, widescreen canvases once more.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'Schmierfett Strassen', 2009, oil on canvas, 120 x 250 cm.

Pankow, Prenzlauer Berg, Weissensse…

The works I’ve seen made in Berlin around 2011-12 feature flowers and gardens. Rather than verdant splendour these works appear ochre and autumnal, traced by whisps of wilting stems or the chaos of overgrowth. When discussing these works you often mention the presence of Berlin and its history, almost as if it is an underpainting. How did Berlin effect your paintings? Does the history of places often inform your work?

There is a painting by Watteau, ‘The Embarkation for / Departure from Cythera’. The best is in the Louvre. There’s a lesser version in Schloss Sanssouci in Berlin. Cythera is Aphrodite’s island, the island of love. The title declares an unknowing – we do not know if the figures are moving toward or away from love. This ambivalence of intention, the setting of figures within imagined landscape, and the influence of Watteau’s use of the gaze, formed a springboard for the work you mention.

I wanted to paint landscape but every time I ventured into the countryside around Berlin to think, I was met with layers of unimaginable horror. Not only was death so recent in the soil, but I felt the fear of post-war Eastern bloc as well as armies advancing, and death marches and the knowledge that every green space would have been forbidden to the man I walked along with and was expecting to marry, who was Jewish. I wasn’t at a place to enfold that in my work. It would be different now. It has literally been enfolded in me – my daughter’s grandfather escaped to Britain on the Kindertransport.

Hannah Murgatroyd,'Cythera', 2020, encaustic & pigment on board, 28 x 36 cm.

It’s funny you pick up on the chaos and dwindling colour in those paintings. That time was a hard time. My body and soul had collapsed from existing so long with undiagnosed chronic conditions – with which I still deal. Despite being on the skids I painted on old bedsheets, I wrote a novel. I suspect I was painting my way back to England, the original isle I’d spent so long escaping from. I grew up on Dartmoor which is a circle within a county within an island. I attribute these geographical concentrics to my sense of narrative as circular, unending. Landscape isn’t benign here. You can see the white sails of Plymouth from the hill above my village. The docks – Sir Francis Drake, monarchical rule, adventure, colonial enterprise, the trade of enslaved people, rise and fall of empire, bombs and fleets of world wars. An island’s coast is symbolic of ebb and flow, of encounter. Encounter is at the heart of Watteau’s painting – and mine. I don’t paint Britain. I view landscape as a feeling and a symbol. Julie Mehretu and Neo Rauch both inspire me in how they embrace the history and trauma of place in their painting, with depth and vitality.

Now I live in Bath. Of late, a more ancient sense has been running through me of Roman Britain overlaid on ancient Britain, swinging behind the Regency façade. The land I stand on urged me to return to painting Aphrodite and Cythera, to the Leipzig and Berlin work.

There is No Distance from the Body to the World

The figures in your work seem deeply connected to the spaces they inhabit – engaging with, sensing and feeling them. Is this something you experience in your own relationship with the world and do you actively aim to communicate this in the work?

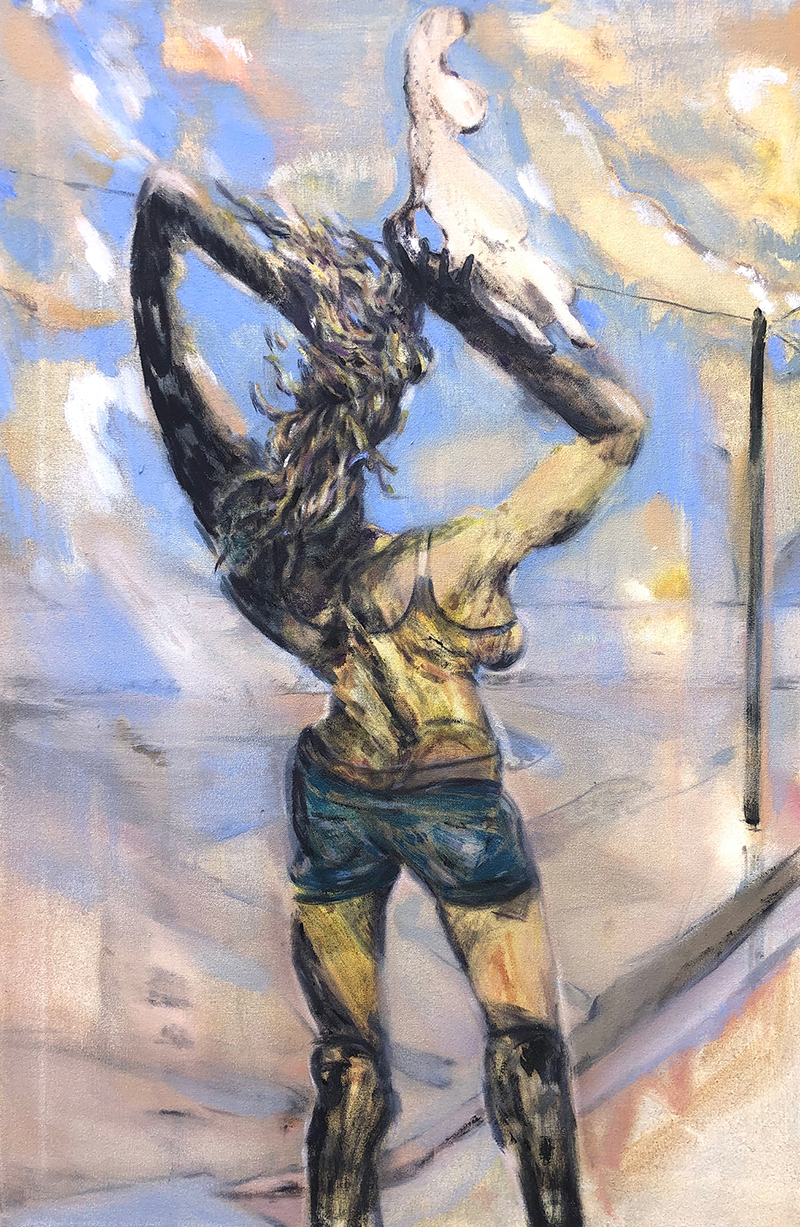

I originally wrote that line in Leipzig in 2009. “There is no distance from the body to the world. Internal, external and imagined space is an undivided concept, unified then transmuted through the body.” I perceive the body as a centrifuge, the vital force that separates and meshes the disparate sensations of being-in-the-world. This is how painting, drawing and writing operate for me, and though each work I make stands alone, were you to put them together in a room, a narrative almost held in the air is what I imagine plays out between them. Within one painting, as I make it, I move from historical references, to internet searches, to lived experiences, to recollected sights, to painted gestures that almost rip the whole thing open. Each painting contains multiple layers of thought and action sifted within its depths. Perhaps, it is past, present and future that settle eventually on the surface.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'There is No Distance from the Body to the World’, 2020, oil and acrylic on canvas, 76 x 51 cm.

Völvas

When I look at your paintings I think about how knowledge can reside in a body. I sense this through the fluidity of your mark making and how this communicates your own tacit knowledge. I think ‘embodied knowledge’ is also referenced through the figures you depict (Seeresses, Heroes and Goddesses). Not only is this knowing physical, it also feels female, intuitive or even pre-cognisant. What is the significance of figures like Völvas for you and do you feel that your painting explores feminist forms of knowledge?

Völva is a word the painter Anna Isley gifted me. I always felt ancient. I could walk out on the hills and touch standing stones. Did that put me in touch with sensuality from a young age? In my life and art I have pursued eroticism through bodily self-possession, existing beyond any external gaze. Female self-possession is sadly still a radical act, still interpreted as an invitation.

The characters’ eyes never look outward in my painting, a conscious liberation from the possessive gaze of the viewer, male or female. I like to think I hand them the freedom of a painted world, impossible to achieve in our own. At Lychee One last year in Marcelle Joseph’s ‘Monster / Beauty’ exhibition, I showed some portraits on aluminium of historical female figures whose tale is tied to the gaze – Susannah and the Elders, Aphrodite of Knidos, Lady Godiva – an ongoing series. When I paint a solitary protagonist I imagine her holding her own gaze – disregarding of audience. Her impetus is discovery, or revelation. Illumination is possible only from inside the self. I don’t especially understand definitions of masculine and feminine. I prefer to think of traits of toughness and tenderness, interchangeable between the sexes. That is my impetus when depicting the figure.

Hannah Murgatroyd, ‘I Am What I Desire (Godiva)’, 2020, oil & acrylic on aluminium, 70 x 50 cm.

Cabbages

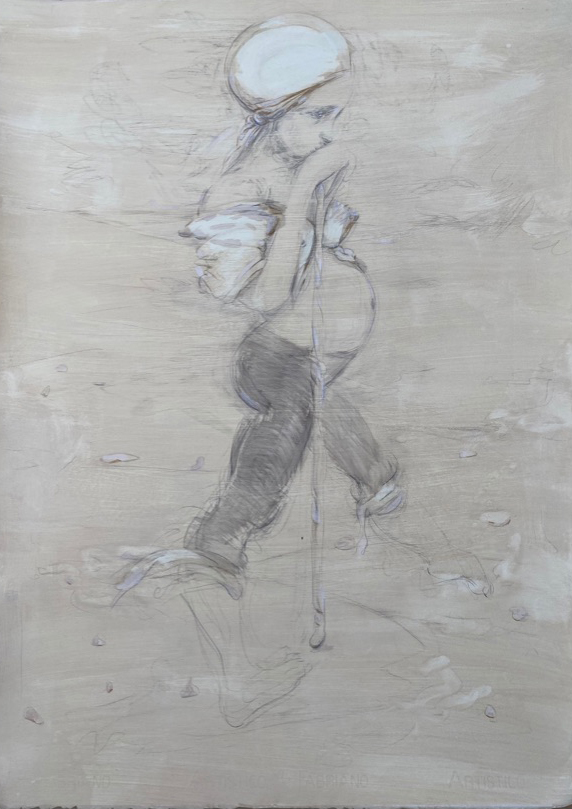

Who is Dörfchen, the character that occasionally appears in your work?

The fool. Probably me, the village girl, stumbling, dumbly persisting, ignorant of shame, hopping along with her lovely body.

Heroes

I find your paintings deeply affecting because of the ways you present your protagonists. We are with them on the journey, gazing out onto vast, challenging territory (Circadian); admiring their confidence, ease and freedom (I Am What I Desire (Godiva)); or empathising with potential feelings of heightened emotion or vulnerability (Hero). How do you manage to communicate emotion or elicit empathy within your paintings? Have you developed technical and formal strategies that allow you to do this or do you feel you can intuitively capture this in your work?

The body seeking ways to be free is pretty much what I paint. Sometimes that body shows its wear and tear on the surface. Sometimes it's smooth. I've lived a raw life. There is a hermetic seal in the studio that returns me to it, but it is through painting that I also make peace with it. Yet don’t assume that my story is the one that matters. I am against women being guided to make work as a confessional as it suggests a benediction is sought. This is why I call what I do an autobiography – of sorts. I am certainly an unreliable narrator. I have lived a lot of lives. Last week I bought a secondhand copy of La Batarde by Violette Leduc to reread. It smells of cigars. I love opening it. Smells like my childhood. I feel at home in Leduc’s writing, as I do in Jean Genet’s. I recently read Annie Ernaux’s The Years. How each writer uses their life as an incense-heady autofiction is closest to how I could describe how I approach painting. I don’t have any strategy. I feel life intensely – yet – I paint toward hope.

Hannah Murgatroyd, ‘Hero’, 2019, oil & acrylic on linen, 200 x 200 cm.

I wanted to be a filmmaker

In your recent piece for Turps Magazine (Issue 23) you begin by stating, ‘Once, I wanted to be a filmmaker’. At different times you also mention Lars Von Triers’ film ‘Dogville’ and the 1949 cartoon ‘A Haunting We Will Go’ as visual references for works. Do film and moving image form an enduring reference for your practice? Does cinema offer you things that Fine Art cannot?

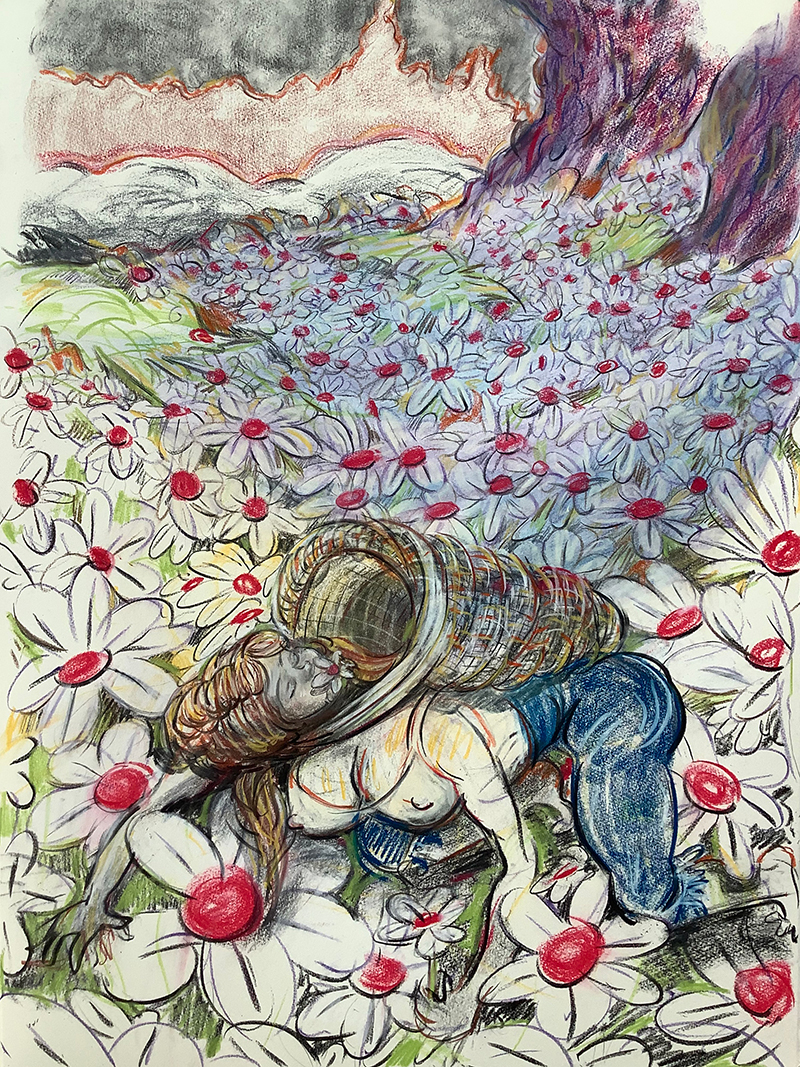

I grew up in rural Devon. There wasn’t any art. But I was an insomniac adolescent and terrestrial television showed movies like Badlands in the middle of the night. Movies were my visual fodder. We lived near Dartington Hall which showed art house movies. I made my father take me to see My Own Private Idaho for my fourteenth birthday. God I loved that film. He liked it because he likes Shakespeare. Cinema was violent, desirous, curious, narrative and atmospheric and showed me that art could reflect one individual’s fantasies. It offered me ways to imagine the world with a vigour that the little art I was exposed to in Britain did not. I loved the concept of Von Trier’s Dogville, that you don’t need buildings to convey buildings, chalk lines will do. It spoke to me of when painting is really working – intimating rather than representing.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'Heart on Sleeve', 2019, chalk pastel on paper, 76 x 56 cm.

Denial and Omission

These words cut through to the surface when talking about your work. You use them to discuss the absence of images of women giving birth; a dearth of representations of pregnancy, and perhaps by extension, the unexplored complexity of what it means to be fertile or maternal. How has your experience of pregnancy and motherhood affected your work and thinking?

We forget that the maternal body is present throughout the span of a woman’s life, whether she gives birth or not during the years of fertility. Complex, invisible and private, hers is a body made fierce by choice and circumstance. I had avoided the pain of painting any of this, living two decades with the grief of being childless. That I was carrying a child was a shock, having thought I’d passed my fertile years. Pregnancy reconnected me with the vital force of the body, and the importance of embodied drawing and painting. I will tell you the truth of how. One night travelling in South East Asia, I thought I miscarried. I mourned for 24 hours before reaching a hospital where it was surreal to find my daughter’s life force had persisted. My pregnancy became an emphatic emblem of survival which continued as a concept as I came close to death in giving birth and entered the first lockdown of 2020 in a state of post-partum PTSD. Instead of being afraid of the hallucinations and the pain, I realised how exhausted I was living in a survival state, that it had been my modus operandi since adolescence. I saw that the body as survivor was at the crux of my work. I became alive to my interior. It is my daughter’s existence I have to thank for this.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'Kyrie Eleison', 2020, Silverpoint and pencil on paper, 76 x 56 cm.

Education

I am interested in your route to becoming an artist. You studied a BA in Illustration at Brighton, an MA in Visual Communication at the RCA and an intense year of post-graduate study at the Royal Drawing School. Why did you initially decide to study Illustration rather than Fine Art? In retrospect do you feel that these courses gave you learning experiences that a Fine Art BA or MA would not have?

I don't know whether I’m a lesson in tenacity or stupidity. I ran away from home at 16, dropped out of school. I was living alone in mid-90s London, studying art and English. Someone said you should apply to Illustration at Brighton so I did. I thought Art was just art, I knew nothing of disciplines, only wanted to go somewhere I could be free to be me. I was always working with narrative, but never like an illustrator. Narrative as an open, ranging event. I wrote, I drew, I took photographs, I painted. I do wish someone had taken a look at what I was trying to do and said get yourself to fine art. I spent hours sitting on the floor in the library at Brighton, gems I remember finding were Ask Dr. Mueller by Cookie Mueller, Written in the West, a book of Wim Wenders’s photographs, Kathy Acker’s Blood and Guts in High School. This was before the Internet really kicked in. You had to dive for knowledge.

In 1997 I took advantage of an exchange program to MCAD and lived in Minneapolis for 6 months. That started my love affair with America, which only stopped when I ran out of money to travel when living in Berlin. I have a lock-up, I hope in there all my work from the American years survives, Super 8 and slide film from the summer of ’98, partying on the Lower Avenue East Side with music scenester friends, road trips across the Midwest. You know, I always said I had to live a life so I’d have something to write about. I think a lot of us latterly defined as Gen X viewed our lives as the narrative arc. We were performing purely for our audience of friends. We were pretty anti-career. We just did shit. Some people got famous. Some people died. Maybe that’s just what being young is.

At the RCA I wasn’t even supplied a desk for the first term, I was advised to ‘go work in the library’. I’m pretty reactive in institutional situations. They don’t suit me. Or I don’t suit them. I found solace in the Drawing Studio, wrote poetry with Apples and Snakes and roamed the Thames. I knew I was seeking something, but was too drunk and afraid to talk to anyone about what that was. Drawing from life, from the figure, from landscape, was anathema at art school at that point. I won the major drawing prize at the RCA but the head of the Drawing Studio said to me going to the Royal Drawing School would “ruin my drawing”. I had to battle a lot of prejudice. It was a lonely path. The RDS gave me licence to simply draw. It was a balm. In one class, Thomas Newbolt said to me “you draw like a painter”. It took until my residency in Leipzig in 2009 to find out what it meant. But that sentence changed my life.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'Daughters, Come Aboard', 2017, oil on linen, 120 x 140 cm.

Chest-Baring

Following on from this you have mentioned that ‘the main characters I met in the painting depts of the 1990s were chest-baring inadequates giving sad girls STDs in between daubing indulgences & smoking roll-ups’. Do you feel your work is ever in conversation with these mythical daubers? Do they still linger in Art Departments?

I went through education without hearing mention of Dorothea Tanning, of Lubaina Himid, of Lee Lozano (and I should just insert etc, etc, etc. here). A lot of my painting education came courtesy of my American boyfriend in the early 2000s and getting to see seminal shows like WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution at PS.1 in 2008. I think even if I had studied painting in a school, it’s less likely these painters would have been mentioned to my generation. The past six years – really since the explosion of Instagram – a completely different climate to paint in has blossomed. I currently mentor an intergenerational group of painters at Turps Art School and see so many extraordinary, risk-taking painters out there, painters unafraid to connect with emotion — from tenderness to rage – three established British painters I am consistently excited by are Chris Ofili, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye and Jadé Fadojutimi. There’s no excuse in the UK today to teach painting as a limited form.

Hannah Murgatroyd, ‘I Would Not Know Who I Am', 2013, oil on canvas, 180 x 220 cm.

Drawing

Where is the place for drawing within your practice generally and within the structure of your paintings?

It is rare I begin painting without making a drawing. A drawing is the first line opening the story. Pencil, ink and brush, charcoal – whatever makes the mark – pulls the image from this private place. The unconscious, I guess. To touch my hand upon paper is to glimpse what Art might be. One reason I like to paint on clear primed canvas is the surface remains closest to paper and when a painting retains the sensation of drawing, is when I am most at ease. My line, my gesture, leaves its own cognisance on the surface but is never fixed, a movement similar to the shifting state of being alive. I taught drawing in various institutions from St Martins to the Royal Drawing School between 2005-2019, but had slipped away myself from drawing from observation. During this winter’s lockdown I have participated in figure drawing groups on Zoom and it has brought me back to a central urgency – that to represent the human is an attempt to bear witness to what it means to exist in the world.

Hannah Murgatroyd, ‘Lay Your Body Down’, 2019, oil & acrylic on linen, 200cm x 200cm.

Future

What are you currently working on or thinking about?

Lockdown, combined with new motherhood wrenched my working practice apart. I had to give up my studio at Spike Island, and worked in exhausted fury at home during my daughter’s nap time, forcing out small paintings and drawings. Thankfully, I connected with Ceri Hand and she gently mentored me through this transition. I finally have a local studio and have resumed a cycle of painting that picks up those tempos I established over ten years ago. Perceptual sensation, landscape, the figure – solo and in groups – and now, the emergent subject of the maternal body. A lot of colour, translucency and opacity. The body melding with the world. I sense it shall involve resurrecting many lost paintings, much lost writing, many lost years. Chronological time makes little sense to me, and we have become so used to the evidence-in-the-moment that we forget that art - and life - is a long, slow absorption.

Hannah Murgatroyd, 'Island', 2020, oil & acrylic on linen, 61 x 76 cm.

Friends

Finally, which artists do you look to and appreciate from art history or our present moment?

I haven't seen a show in person since Lee Krasner at the Barbican as I gave birth a week after. What an astounding exhibition – everything that being a painter is about. I feel allergic to my iPhone but I want to be part of this world that is being pulled apart and put together as we speak. Some shows I wish I’d been able to see in person in London would be Tu Hongtao at Levy Gorvy, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye at the Tate, and in New York, Rosa Loy at Lyles and King, David Byrd at Anton Kern. Some artists who keep hitting me in the heart are Tau Lewis, Joan Mitchell and Enrique Martinez Celaya. In the midst of last year’s shocks, I discovered Ariana Reines talking on the LA Review of Books podcast. I really appreciate her persistent quest to expand our universe.