Twist

Rebecca, it’s wonderful to talk to you about your work and explore what happens under the surface of your dramatic images. I can see that you’ve been making work for a long time, with your BA undertaken in the mid 90’s. Have you always made work that explores the construction of gender? What sort of twists and turns has your practice taken over time?

I’ve always been interested in ideas and stories as much as painting and drawing. And I also remember being a small child and having these revelations about how society treats us, and how we begin to think about who we are, and how we should behave, or are expected to behave. It was like a light bulb going off in my tiny head back then, and it was too much to really take in. I had a Peter Pan phase, and a flamingo phase (I can’t remember now in what order): neither were allowed to take hold. And so I got dumbed down, but I still had this funny elf left inside of me, with knees jointed on the back (where they should be), coral-coloured wings and a talkative shadow.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Fish Witch', 2021, oil on canvas, 153 x 100 cm.

It’s taken me a long while to assemble my work and see the bigger picture. Partly because there is this sprawling nature to my way of thinking, and partly because I didn’t have the confidence to stick to my ideas. I had a big gap between my BA and MA where I’d spent 12 years working as a set painter for film and T.V. In between, I made work sporadically... but ultimately, I lost my way. Then somehow, I finally scraped myself together and got into the Royal College. I was amazed just how focused, switched on and confident the younger set were. I graduated in 2009 at the tail end of the financial crash. It was a bit of an anti-climax for me. I’d started making these massive paintings of naked men which caused lots of heated arguments. I’d probably shot myself in the foot a bit. I remember hearing this gallerist wanted to speak with me. But when we did, she said “I want to congratulate you on your work! – but I can’t possibly show you!”

I felt really isolated after college and lost my bottle. Most of my time was spent painting sets for reality T.V. shows or decorating millionaires’ mansions in varying shades of Ecru. I’d really got to the edge of giving up my dreams all together, but I kept persisting, exploring all sorts of themes, as if trying to dig myself out of a self-inflicted trench with an inflatable spade. But with time, and lots of digging around, I started to realise there are cyclic patterns within my work, and gradually started to get back into gear.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Fish Licker', 2021, charcoal and ink on paper, 65 x 50 cm.

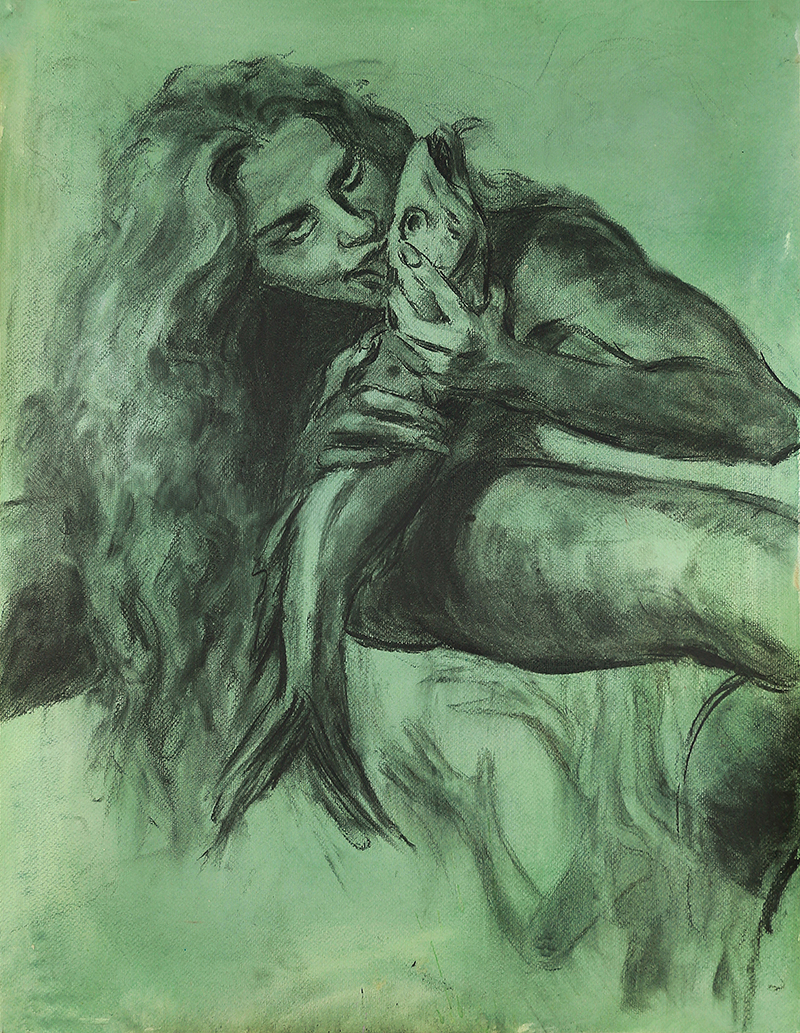

Green

What triggered your fascination with Green women? Following on from that, what are your feelings about these verdant creatures? Do you identify with them? Is there an element of wanting to ‘re-stage’ their long played-out scenes and give them center stage?

They emerged through a filmic dimension. I’d been making some drawings from horror films and trying to make them as faithfully as I could, just as a fan artist would do. I’d been looking at Giallo film with it’s intense, artificial, and symbolic use of colour. I had been drawing from zombie films and possession films, Hammer Horror and ‘witchsploitation’, and all the way green faces kept boiling up out of the gore. All these interests also led me to think about the performance of a character, particularly of an exaggerated performance marked by strong emotion and a striking, over-the-top visual aesthetic, and so the green skin just naturally crept in.

The wonderful staginess of Margaret Hamilton’s performance as The Wicked Witch of the West in the ‘Wizard of OZ’ lives up to the luridness of her face paint. I began to think about the connection between witches and the colour green: There’s the obvious side, to do with nature and enchantment, and then there’s the foul side: mould, decay, snakes, poison, and of course aliens, who have inherited their lurid complexion from the trickster, or fairy. Once I’d started thinking about green women they began popping up everywhere!

The Green Women have got a sense of humour about themselves, for me there’s a sense they are both poking fun at their own history and revelling in it. I sometimes think there’s nothing much cornier than a green face, and it’s the worst thing I could paint, but that also makes me laugh! It’s also about a retina singeing intensity, they want to be noticed, and maybe that reflects my own desire as an artist to be noticed or put something vivid into the world. The characters get to out-perform themselves having been given centre stage, and they get to embody their performance in a self-reflexive way.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Emerald Esmeralda', 2018, pastel on paper, 100 x 75 cm.

Fandom

Your Instagram feed is a library of pulp, horror and B movie glamour. Can you tell me about your image research: Where do you find these references? Are you a fan? Is there a line between obsession and critique?

I collect books on film posters, book cover illustration, fantasy art illustration, comics and pulp fiction book covers. If I had my own house I would collect movie posters, but I don’t have the room. I do a lot of research online and people send me images too. My material really just comes out of things I enjoy. I love the particular quality of analogue, pre-CGI horror and fantasy film: a world of pyrotechnics, prosthetics, and puppets. The exaggerated, visceral, almost comic book colours, deep shadows, grease paint and special effects are used in a spectacularly physical way, and hence relate to a painterly world. When I’m looking at these kinds of images I’m engaging with them both aesthetically and reflectively, so I think while I’m a fan, I also exert some critical distance. Part of the enjoyment comes from reading behind the image, from recognising the many attempts at appearing in the world and what they tell us about things like gender, class, and sexuality. Whereas I like to read pop culture critique, I don’t, however, want to make my work so literal, and I don’t want to be didactic either. Art has to come alive to be potent; have multiple readings and be willing to pervert the familiar order.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Mistress Mantis, 2020, oil on board, 64 x 44 cm.

Artist as Anthropologist

There is an element of social anthropology to your practice; an in-depth exploration of how women (and sometimes men) are portrayed, drawing connections between Greek mythology, medieval morality and pulp fiction. Do you ever see yourself as an anthropologist as well as an artist? If so, what does your reference material tell you about our culture?

My computer is full of hundreds of files with titles like Russ Meyer’s busty beauties, or European swamp witches, or Snake women in B movies. I make archives which are organised by my own forms of systematisation, I sometimes re-organise my images into different groupings according to my changing ideas. This process allows me to fantasise into the subject and create connections across wide areas of culture. Fairy stories, folkloric myth, Horror film, Fantasy, Sci-Fi , fan culture and Genre paintings of the Dutch golden age all contain stories produced in the common vernacular. They are based on a formulaic set of tropes and exhibit forms of behaviour painted with a broad brush. Common social fears and desires are given an uncensored expression either directly, through undisguised exploitation, or through fantastical metaphor.

I think there are so many things this material can tell us about our culture. At the heart of some of my recent investigations is a young, forthright woman coming up against societal pressures, and the hallucinatory stories chart her attempts at liberation (like our cryptic dreams, which attempt to reorganise our waking world by summoning archetypal images). All this material proves how the imagination is inextricably intertwined with our moral conduct and identity. We have a strong collective appetite for play-acting these vivid parts, and these cultural characters help us make our futures and come to terms with change.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Lady Gaga flying to the Brocken on horseback', 2017, mixed media on paper, 53 x 60 cm.

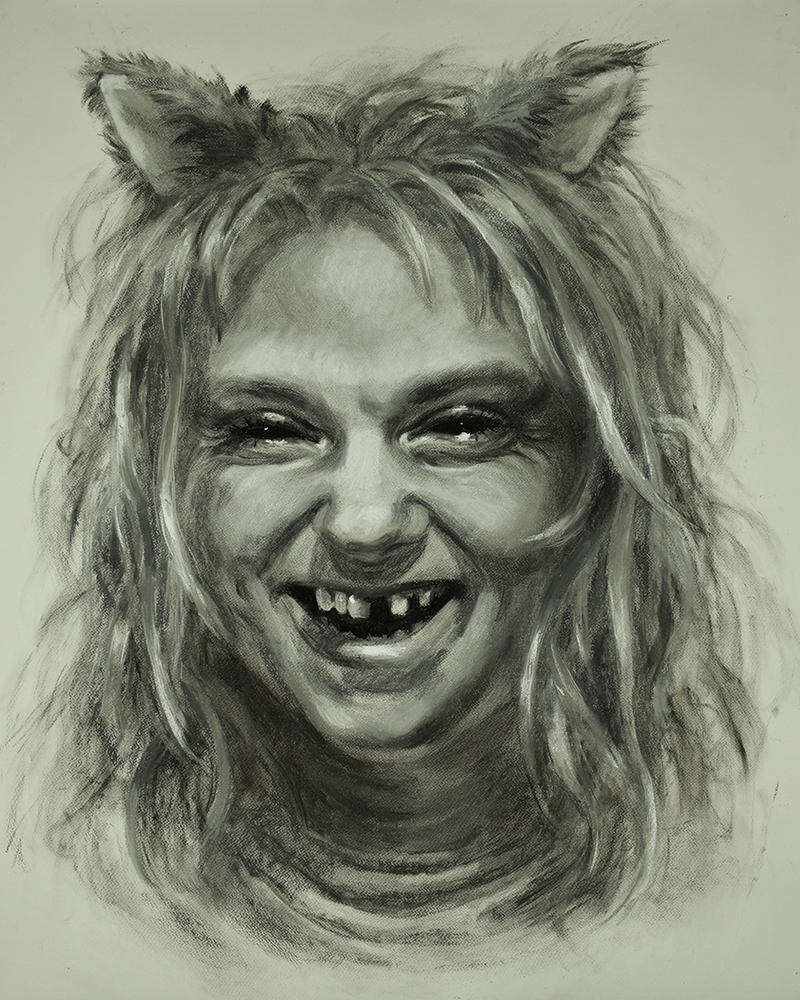

Shoot

I have seen an image from a photoshoot where you were working from a model; lit, dressed and fully made up in green greasepaint. Do you always develop your drawings this way? Is make-up, lighting, direction and photography an important part of your work?

I use a mixture of approaches. Sometimes I develop work from film stills, but I found particularly with my ’Green Women’ series I needed to work with models and direct the action. Given that there are a lot of reference points to artificial constructions of identity, this way of working makes sense. I use friends to pose in the shoots and give them some direction, but also, I like some of their ideas and personality coming into it. I will imagine my own mini film script and use props to animate the action. There is an obvious overlap with cosplay, which is also something I find interesting as a spectator and something I have thought about working with more directly in the future.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Crème De Mented', 2018, pastel on paper, 75 x 55 cm.

Skill

Your work demonstrates such skill – has the language of representational drawing always been important to you?

I used to think I had to come up with some new novel approach, that my style wasn’t unique enough. I think there’s naturally that pressure at art school to reinvent painting. It took me a long time to realise I already had my style, looking for something new was only supressing me. I think my style comes out of wanting to strike a balance between making something appear believable, and keeping some element of expressiveness, keeping my ‘hand’ in the work, so to speak.

I’ve always liked working with charcoal, and drawings or pen-and-ink preparatory sketches are usually my favourite pieces from Renaissance artists. I always want to be direct and honest with my material. I’ve always loved illustration too, of all different forms. The common appeal of hand painted advertising, for instance, is that it tells a story and it’s easy to understand, but it conveys so much more about society and popular desires of the time. These lo-fi forms are saturated with the shifting cultural fantasies of ordinary people.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Into the wilderness', 2009, oil on canvas, 200 x 250 cm.

Funny Girl

It feels like there is a wrestling match between sincerity and humour being played out in your images. For example; Into the Wilderness (2009) is incredibly kitsch in content but executed beautifully and without sarcasm. Can you tell me a little about your approach to humour? Do you find your own works funny sometimes?

I painted ‘Into the Wilderness’ while at the RCA. The painting was developed from a photoshoot I found in a copy of Playgirl Magazine from the late 1970s. It was a painting I enjoyed making a lot. Putting in the little jokes and references are the details for me that interject a painting with life, (like the bit of straw between the toes which parodies the famous Jane Russell poster for ‘The Outlaw’). I think the sincerity you’re talking about maybe comes from my paying homage to particular kinds of illustration. With ‘Into the wilderness’ I was looking at men’s action-adventure pulp magazines from the 1950s and children’s illustrated Sunday school books (the kind with pictures which fade out at the edges with beatific images of Jesus surrounded by his worshippers). But I also had a lot of fun making some stylistic references to painters popular at the time like Peter Doig and Sydney Nolan. I guess I was having a dig at canonical art history, at the overexposure of so many male painters, and historical surfeit of supine female nudes. So, I think there is an element of satire in some of my work but delivered with a spoon of honey. I don’t want to drive ideas across in an aggressive or cynical way, so I use my own brand of humour. It’s difficult to know how it comes across to someone else, but I just use the approach that feels natural to me.

Rebecca Parkin, 'The Fool', 2018, charcoal and pastel on paper, 90 x 71 cm.

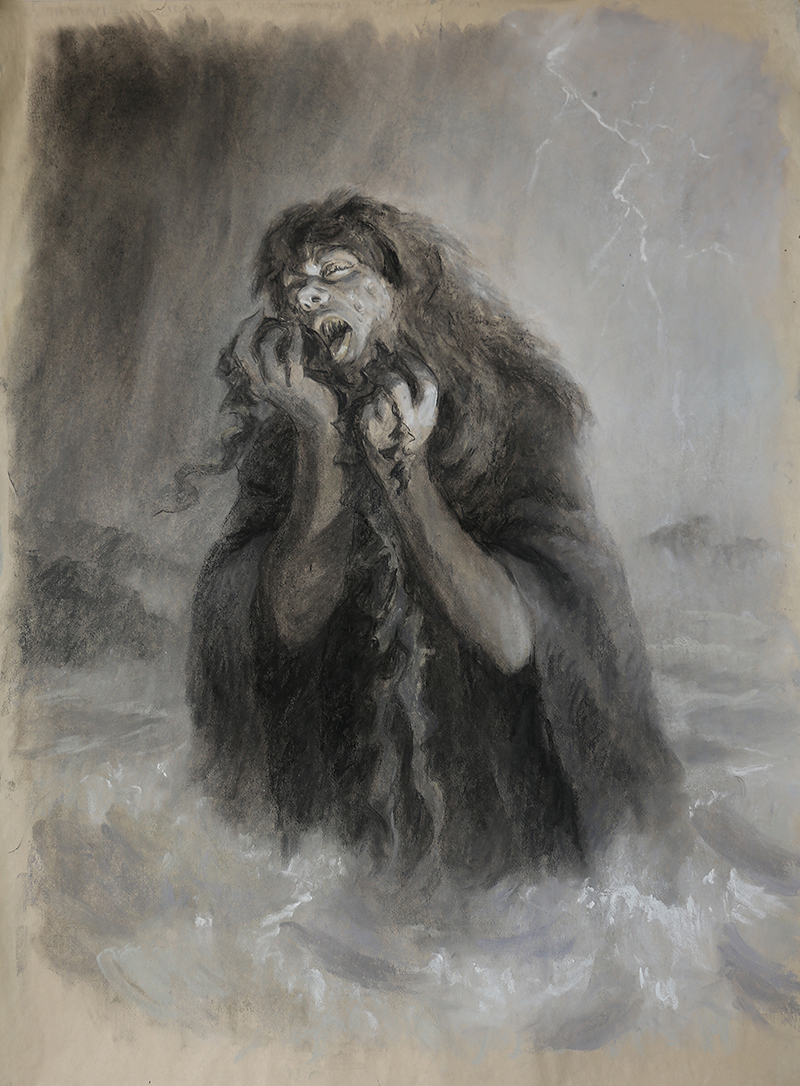

Witchcraft

The witch is a strong feminist symbol which tells of a history of violence against women by the state, church and individual. The witch has ‘other’ knowledge; empirical knowledge of plants and the body, of sex, childbirth, death, and magic. How do you define the figure of the witch and why is she important for you?

The figure of the witch interests me as she encompasses manifold and contradictory elements. She symbolises the power and agency of women and the fear by others, of that power. She has been used by both radicals and reactionaries in turn, as an emblem of feminism, and as a way of deriding women. Her filmic incarnations from sexy sorceress to hideous hag, have charted a revealing history of how society perceives women. The celluloid witch takes flight with the rise of feminism, spiralling through the sky with baroque twists and turns in tandem with both sympathetic and misogynistic scripts. I enjoy the subversive side of her most; the wicked or devilish behaviour of Disney’s witches/villainesses, and their resourcefulness and cunning. Though often she is used in sexist narratives, punished and scapegoated, I see her essence as a transgressive character and a symbol of female persecution engaged with overcoming oppression. She presents a perversion of the system, she plays dirty, and her tools of magic, mastery and deception make her a highly wilful and proactive agent in her own story. She represents for me a strength, and a refusal to go along with the status quo.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Storm Spirit', 2021, charcoal and pastel on paper, 88 x 64cm.

Friends

Which artists excite you from the past and present?

One of my favourite painters is Frans Hals for the brevity of his marks and incredibly acute sense of aliveness in his faces. I love Goya too, especially his etchings and drawings of witches. I developed a sudden obsession with Renoir’s late paintings of delightfully excessive bathing women recently. They’re a bit vulgar and kitsch but wonderfully physical like a romantic precursor to Robert Crumb’s women. I’ve always enjoyed the acerbic-ness and savage wit of Dawn Mellor's paintings and the compulsive mining of popular culture by Jim Shaw and the late Mike Kelley. There are so many brilliant new artists emerging today - I love the voluptuous femininity of Izzy Wood's velvet paintings, the playful concoction of worlds in Kati Heck’s work and explicitness of Jenna Gribbon’s nude portraits of friends.

Rebecca Parkin, 'Murderous Mermaids and Watery Witches', 2020, acrylic on canvas, 137 x 100 cm.

Future

What are you working on at the moment?

I’ve been looking at the language of B-movie posters for a while, the rough cut and paste organisation of space and the surprising narrative collisions which come out of that technique. I’m experimenting with a similar format, and I want to see where that goes. I’ve had several comic books and fanzines in the making and I’d really like to develop some of those. There are also several other projects which I began this last year around a mermaid theme, one is a series of charcoal drawings based on Daryl Hannah in the 1984 movie ‘Splash’.