Invention

Rita, thank you so much for taking the time to respond to my questions. You make sculptures, instruments, performances, drawings and more. Before getting into the nuances of your interdisciplinary works can I ask if you consider yourself as an inventor, and how much ‘invention’ factors in your practice?

Firstly, thank you for your insightful questions.

Invention is an integral part of the creative process for me. Invention is improvisation. A gap (or in my case a question) appears, which I want to find a way to bridge, through trying things out and tinkering. At first it can be awkward, but by looking at something from all angles, I make it work, creating a new thing in the process. I think my sculptures are bridges from one question to the next. To keep the questions flowing, I always keep an openness in the sculptures so they never quite settle.

My dad is a toolmaker, and I think because of this, I have been fascinated my whole life by how we invent tools that enable us to make further tools, you have to think a few steps in advance. Tim Ingold has some interesting things to say about invention and improvisation beyond the human world. Spiders evolved (or ‘invented’) the means to create webs from within their bodies. This is such a fluid process, there are strands of possibility flowing through everything.

Rita Evans in her High House studio, 2015. Photo: Fiona Haggerty © Acme Studios Archive. Stephen Cripps’ Studio Award 2014/15 funded by Acme Studios, The Henry Moore Foundation, High House Production Park Ltd and Stephen Cripps’ family.

Instrument

Your instruments take novel forms and can often be played by multiple people at once. They can be percussive, wind or string instruments and to my eye appear to be transported from ancient legend or science fiction. How do you begin building your instruments? Do you begin with a sound in mind?

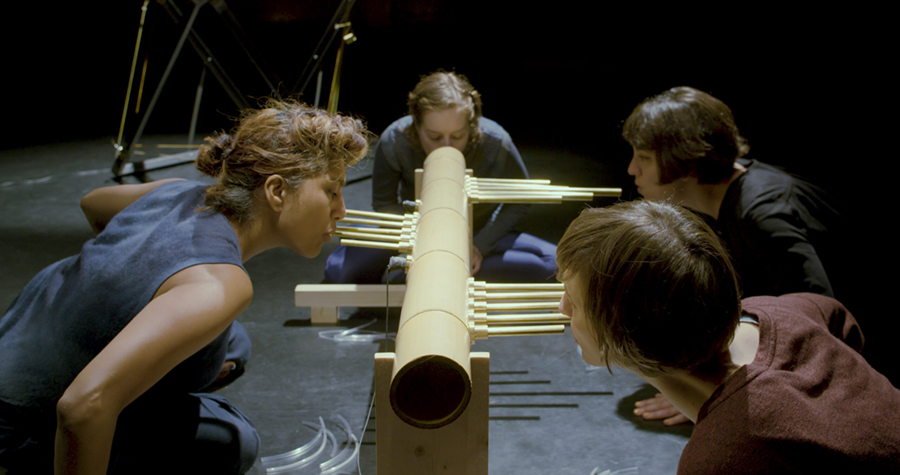

To make a new piece, I have a sound and a movement in mind from the knowledge I gathered from my previous sculptures and I’ll often ask myself the next question - What would happen if…? These questions are based on my curiosity to combine body and material. I work in a loose and open process, looking at something I am making in as many different ways as I can, until the new sculpture and how it is played eventually emerges. This allows for surprising things to happen. I’ll have a plan I work through, by making new combinations of previous sculptures, working a material to its limits, or setting myself the challenge of finding sound where there was no sound before - in this way I am able to take things a little further each time.

The sculpture also has to function as an instrument so it doesn’t collapse during playing, and so I have to try to find a balance of certainty and uncertainty, function and a feeling of emergence. What I love about working in this way is that the sounds and forms created take me into a very fluid world. Each sculpture is its own world. I think this might give them a science fictional appearance, a kind of artisanal workshop of the future.

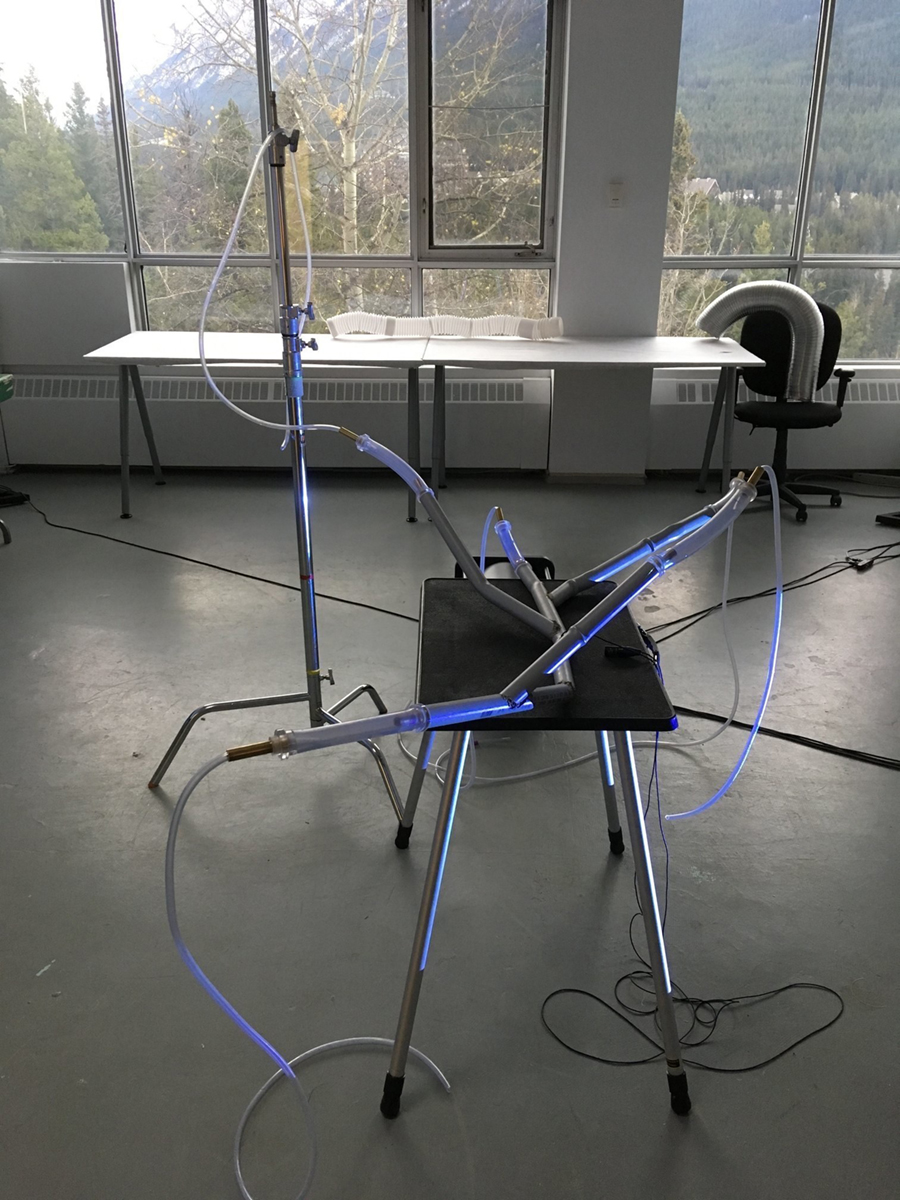

Rita Evans, 'Multi Breath Poly Pipe', 2018, at Banff Centre for the Arts, Visual & Digital Arts Residency. With the support of the Canada Council for the Arts.

The Art of Noise

The ambient sounds made by your instruments bring Luigi Russolo’s Futurist Manifesto, ‘The Art of Noise’ to my mind (1916). Whilst calling for a move away from restrictive Greek and harmonious Gregorian scales, Russolo wants to incorporate all ‘sound’ into the realm of ‘music’ to bring art closer to modern life: ‘This musical evolution is paralleled by the multiplication of machines, which collaborate with men (sic) on every front.’ How does your practice connect to (or deviate) from this canon of Noise music? What is the potential of Noise today, when machines digitally ‘collaborate’ with us on an exponential level?

For me the potential is in the rhythm of multiple different rhythms interacting - (or another way to say this - in the continual shifting of a multiplicity of different things in relation.) In Timothy Morton’s Hyperobjects, he describes an artist who amplifies a windowpane recording it over a long period of time. The recording is sped up to perceive patterns and systems of weather, traffic, allowing us to hear connected systems at play that are bigger (or smaller) than our previous comprehension.

I built many of my sculptures to be able to hear what it sounds like when people focus on a task together, being in or out of empathy and connection with others, the polyrhythms that creates, the sound of group dynamics. With any one of my sculptures, it’s different every time.

I have very recently been collaborating in the playing of my sculptures with machines, that have a strong physical materiality. I alter and interrupt the flow of the machines with my body via the sculptures. I like to work with chaos as a force for composing and improvising, playing with it is endlessly fascinating.

Rita Evans, Threaded Infrastructures', 2019, participatory performance at Archway Sound Symposium.

Painting to Sound

I see that you studied a BA in Painting at Brighton in 2002. In retrospect, do elements of that time in your education filter into your current work? Is there anything painterly in your approach or do you see yourself as operating beyond disciplinary boundaries?

When I look back I seem to have completely ignored any boundaries between disciplines and that seems to be a habit of mine. What I enjoy about painting is that you have a place within which you can move a fluid paint shaped thing about in to create a new type of illusionary space. I don’t think that approach has ended with my sculptures, in painting I was imagining the feel of things, the weight of things, the proximity of different types of bodies. I was also concerned with when the paint dried how I couldn’t then move it about anymore. I don’t use the language specific to painters although it was very much part of my education at Brighton. I have also received a music education of sorts in Brighton in the 2000s, we had some great promoters there who brought in incredible bands coming to play at that time. I remember seeing a band called Storm & Stress, a free jazz math rock band from Chicago and I spent the gig thinking about tipping points between one place and another, wondering here what defines boundaries. I’ve aways thought about three dimensionality and the fluidity of illusory spaces that can be revisited again and again.

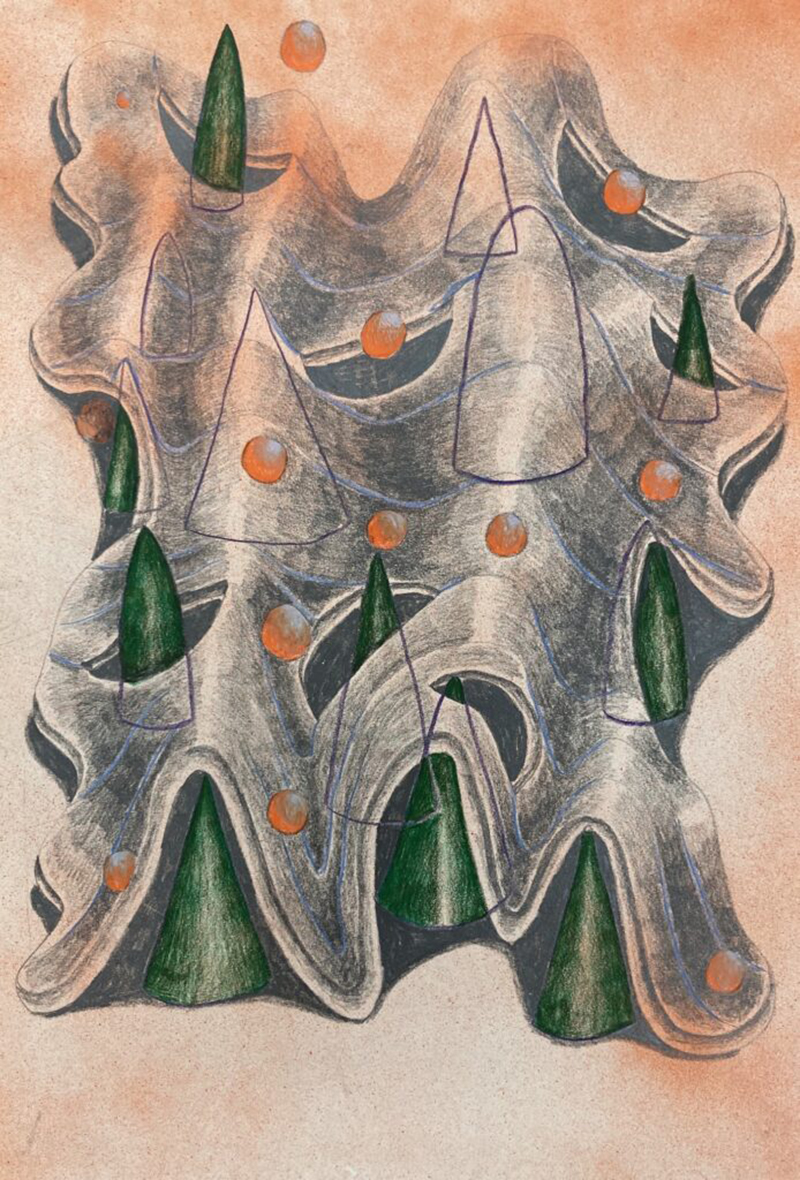

Rita Evans, 'Gathering 1', 2020, graphite, colour pencil and spray paint on paper 57 x 38 cm.

Matrix

Matrix derives from the Latin word for ‘Womb’. This word appears in the titles of your work. You also seem to work predominantly with female performers and mention references such as weaving, ‘women working in war time telephone exchanges’, and female mythological figures such as Greek Moirai and Germanic Norns. Can you tell me a little about the implicit feminism in your work?

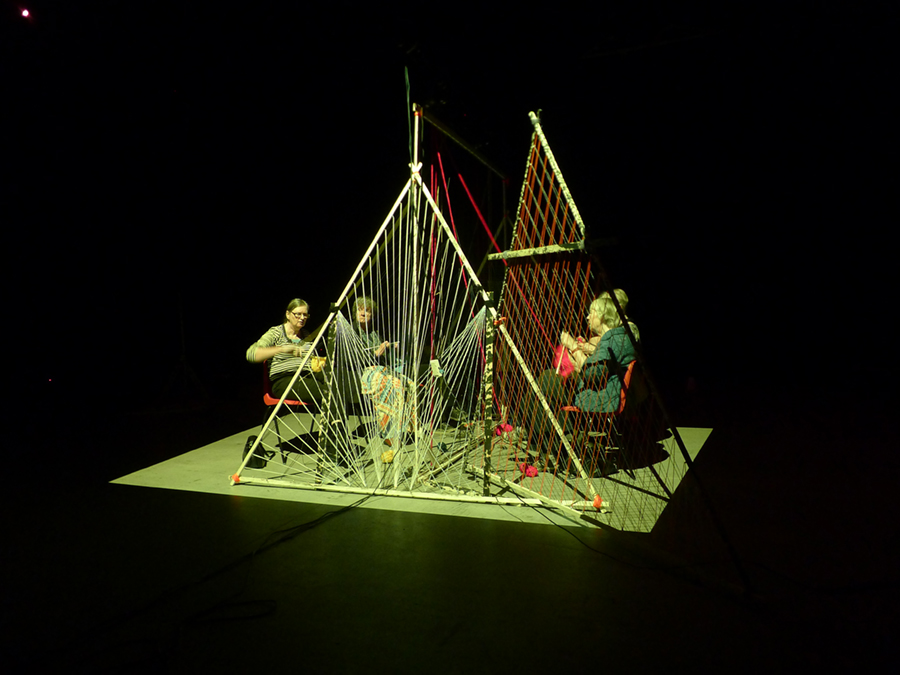

It felt really powerful at that time in 2014 to have a group of women together to play what was quite a fierce sounding piece. With Wool Matrix, I had been reading Sadie Plant’s Zeros and Ones and thinking about technology and gender. Zeros and Ones argues a feminine lineage of hands and minds taking us into the future - from weaving and telephone exchanges to the invention of algorithmic systems - all of which are matrices.

A matrix is a defined space, with an inside and an outside, that has its own logic, and within that, something new is created. For example, a stringed instrument tuned to a certain system on a grid form, that tells a story as it is played. The word shares its root with the word womb, and also in the land, a containment of things. I am drawn to the word matrix because, in a way it is ‘invented’ by women, and it takes us beyond gender.

When I made Coil of Days in 2018/19, I was reading Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation by Silvia Federici. Federici writes about the emergence of capitalism with the witch trials, how women had tried to create or maintain their space, despite opposing forces in society rapidly eroding these, with some brutal examples. The wider message here is about the dehumanisation of a group of people for exploitative purposes. The sculptures in Coil of Days became tools to rediscover space, to sense it carefully and make conscious decisions about where to lay down new lines, rebuild, (rather than block out) in the way you have to put yourself back together with care and self-trust after a life changing event. I had experienced such an event at that time in my personal life and I wanted to make Coil of Days an open process in a safe space. At the time, that felt like a space with other women, trans and non-binary.

I work with all genders, but my work is feminist in that we create an inner space with a strong foundation of collaboration. Then, when we are ready we invite in an audience, who will shift the space we created in all sorts of ways.

Rita Evans, 'Wool Matrix', 2014/5, performance as part of Stephen Cripps’ Studio Award, funded by Acme Studios, The Henry Moore Foundation, High House Production Park Ltd and Stephen Cripps’ family.

Utopia

You have undertaken many educational projects; collaborated widely; been in residence at the Bauhaus and even studied a short course in the Anthropology of Spaces, Places and the Built Environment at Goldsmiths. How much does your practice intersect with Utopian ideals, such as place building and universal creative education? Are there limitations in Utopia?

Utopias are useful spaces when we are aware of our biases, and our limitations on knowledge of others’ experiences. Then we can begin to construct spaces together that might have a message, a use, and that gives a group strength to make changes and shifts. A place that can be revisited whenever needed. When I worked with schoolchildren in Elephant & Castle (Rock, Paper, Scissors, The Drawing Room, 2021), I tried to only respond to their ideas, guiding them to create their own spaces that we recorded so that they could go back to shape them or look at their time together at any time in the future.

In the science fiction of Ursula Le Guin we read about other ways society might be. In her early science fictions she was still working with the old sci-fi image of the male explorer/warrior. Later, she departed from that and created an archipelago of societies, with completely different rules, such as those with no defining gender. In the Earthseed books by Octavia Butler the main character tries to create a new community who believe in how things are continually shaped by change, reflecting the experiences of those who are trying to create and live (to be human) in dehumanising times.

Rita Evans, 'Coil of Days', 2019, performance, still from film. With the support from the Canada Council for the Arts.

Many of the Bauhaus history books feature diagrams of an able bodied white man representing his universal ideals in the image of, well, himself. Much of the more varied and interesting history that was the larger Bauhaus experience was only written about more recently. Elisabeth Otto’s book Haunted Bauhaus talks about intuitive esoteric practices, gender fluidity, and clashes between staff on their wildly differing politics that made the Bauhaus such an interesting and experimental place. All happening at a dangerous time that the extreme right wing was rising in Germany. The many, many Bauhaus women teachers, wives and students, were largely written out of much of the history until recently since documentation has been harder to come by (likely because it has been kept in personal archives rather than institutional ones). For example, much of the foundational course for Bauhaus was based upon the sound, body, movement, colour harmony experiments by a musician called Gertrud Grunow. While her contribution was acknowledged by Walter Gropius, the founding director, she was never made an official Bauhaus Master!

Rita Evans, 'Coil of Days', 2019, performance, still from film. With the support from the Canada Council for the Arts.

Falling

I’m thinking about the way the titles of your recent drawings pierce through the hypnotic atmosphere of their imagery. Titles such as ‘I tried to move in, but it fell through’, ‘My money melted, but that’s ok because so did the bank’, or ‘Basement, available now, fully furnished’ talk so much of our recent material and financial realities and the flip side of creative labour. Can you tell me a little about these images and words?

These were made in the winter of lockdown where I was renting a tiny and damp yet strangely cosy room to save money and find space to figure out, ‘what next?’ and redundancy was looming for everyone. I made the room an oasis for thoughts and plants, so my domestic environment became a portal for my wilder imaginings of new spaces. The plants, the rising damp and water in the sink became gateways to this. I think there’s a strength in finding a personal imaginary space in the things immediately around us when times are challenging. Some of the drawings feature bar charts, I was thinking about abstract imagery in the news, and trying to reconcile that with the effects on everyday life. The drawings picture the challenge to stay broad in a time of closing down. The heavily psychedelic imagery does give me a sense of the claustrophobia of the time.

I wasn’t able to play my sculptures with others during the pandemic, (until I made some socially distanced sculptures) but I thought about one of my sculptures which is a playable piped instrument that combines body with materials, where water droplets from breath vapour change the tones of pipes as they are played. My room, the bank, the instrument, all hermetic liquidy damp existences of multiple singing beings.

Rita Evans, 'I tried to move in, but it fell through', 2020, colour pencil, spray paint and graphite on handmade paper, 29 x 42 cm. Image courtesy of Aleph Contemporary.

Drawing

What role does drawing perform in your extended practice?

I draw to bring very different things together that I have been reading, experiencing and half-made experiments with materials. The drawings can be in the form of diagrams, of sketches for new sculptures at different stages, plans for playing the sculptures (would be scores), some function like lists to help me remember ideas for playing the sculpture so I don’t forget. During my residency at the Bauhaus, I redrew the instrument that I made in situ in different imaginings of Bauhaus spaces that I encountered during my research, the weaving looms, the designs for new fabrics and curtains, the prism glass used in the Dessau social housing estate. The sculpture accumulates all of this over time, as it does after different groups have interacted with it (I’ll draw the outcomes of that too). I think the drawings describe very well to others what I am trying to, much better than me trying to explain it verbally. This is so useful when working with new performers so I always bring my drawing along to a first couple of meetings. They are functional within my practice, but also stand as pieces in their own right. Often when I complete a sculpture it’ll have a constellation of documents around it, including drawings that show the process of imagining the sculpture in different ways towards its current situation. At my current exhibition at The Bauhaus Foundation, the drawings are for the first time exhibited around the object.

More recently I’ve been drawing to imagine sculptures that I’ve already made and performed in different fictional spaces expanding the scope into future potentials.

Rita Evans holds 'Instrument on a Plane of Prism Glass', 2021, colour pencil on paper, 29.7 x 42 cm. Photo from Bauhaus residency studio of Masterhouse Georg Muche. Credit: Yvonne Tenschert. Courtesy of Stiftung Bauhaus Dessau.

Dream Show

You often make work in residency or award scenarios; where a context and (potentially) a set of aims are given. If you had an unlimited budget and could work where and how you wanted what would you do?

I’d build a freeschool, based upon the crystal architecture of the early Bauhaus designs and I’d also make my work there. Does that count?

Rita Evans, 'Matrices and Tensions as Sculpture', 2017, documentation of sculptures in a public workshop, Chisenhale Dance Space. Supported by Arts Council England.

Future

What projects do you have on the horizon?

I am just about to perform a sculpture commissioned by Tate St Ives called Stringing the Matrix, it was originally made in response to the Naum Gabo exhibition there two years ago and was delayed by the pandemic. The sculpture in its static form is currently on exhibition there with my film Coil of Days. I will be performing Stringing the Matrix on the 30th April with three very special guests from Redruth in Cornwall.

I am also working on the beginnings of a new film and performance in collaboration with machines to play my sculptures. This was one solution to not being able to work with others for two years. The sculptures will speak indicating further performative actions. This new strand to my work I have been able to explore all thanks to a grant from the Sound Arts department at the Canada Council for the Arts.

Then in July, I will be at Towner Eastbourne creating a new solo commission called Tuning in a Vacuum. There will be two performances on 16th & 17th July with four dancer/musician performers using three new sonic sculptures. I will work collaboratively with the performers to create a special focused space where we can tune into the subtle shifts and changes of sound and movement, creating the whole space as an instrument that we then invite the audience into. Eastbourne is near to where I largely grew up in Brighton, so it feels very special to be invited to create new work there.

Rita Evans, 'Instrument' within the exhibition ‘Fictional’, 2021. Haus Gropius, Bauhaus Dessau Foundation. Curated by Florian Strob. Photo: Meyer, Thomas, 2021 © OSTKREUZ.

Friends

Finally, which artists (Music or Fine Art) do you look to and appreciate from history and our present moment?

There are so many, it could be slightly different if you asked me on another day, but I’ll list those who in the past and more recently have made an impact on me:

Eileen Radigue (her unfolding slow organic evolving drones).

David Tudor (his Rainforest piece - I think it’s exhibited at MOMA).

Senga Nengundi (experiments with movement and materials.

Harry Partch (he created his own musical pitch systems that are incredible geometric worlds and that’s even before we get to his amazing instruments. His world building takes you into another completely different dimension where you have to reconfigure yourself in order to enter).

Delia Derbyshire (her sheer inventiveness.)

Woody & Steina Vasulka (particulaly Woody’s machines that he built from found technologies).

Takis (chaos, dissonance, destruction).

Lygia Clark (collective performative objects and actions).

Ithell Colquhoun (connecting bodies, to earth).

The Boredoms (I had a lightbulb moment watching the Boredoms in 2006 feeling the power of multiple drumming, and Yamantaka Eye moving these glowing orbs around the stage that sonically shifted the sound according to how he moved).

Sonia Boyce (her collaborative practice and openness to process).

Gertrud Grunow (the original godmother of the Bauhaus).

Joan Jonas (the intensity of her work and it’s connections to body, environment, material).