'Me' is a fiction

Aimée, thank you so much for talking to me about your work. I’d love to boldly jump into the deep end and explore the potential of your work being a call to abandon the egoist traps of art! Your use of Jacquetta Hawkes’ 1949 text ‘A Land’ suggests you’re interested in shedding the ego in favour of embracing a more collective idea of consciousness and creation. In connection to your recent solo show Whitehawk Camp at Mackintosh Lane you quote: ‘‘Me’ is a fiction, though a convenient fiction and one of significance to the consciousness of which I am the temporary home.’ Does this de-emphasis of ‘me’ relate both to the contemporary art world and to wider ecological concerns?

It is difficult to be critical about the commercial art world without feeling like a hypocrite, as I work within the system I am to some extent complicit. However, I think it suffers in the same way broader society suffers from the legacy of neoliberalism and being bound to late capitalism with emphasis on individualism and consumerism. I think there is immense pressure for artists to promote themselves as a sort of celebrity or brand which leaves little space for creativity and often results in something bland, repetitive and conservative.

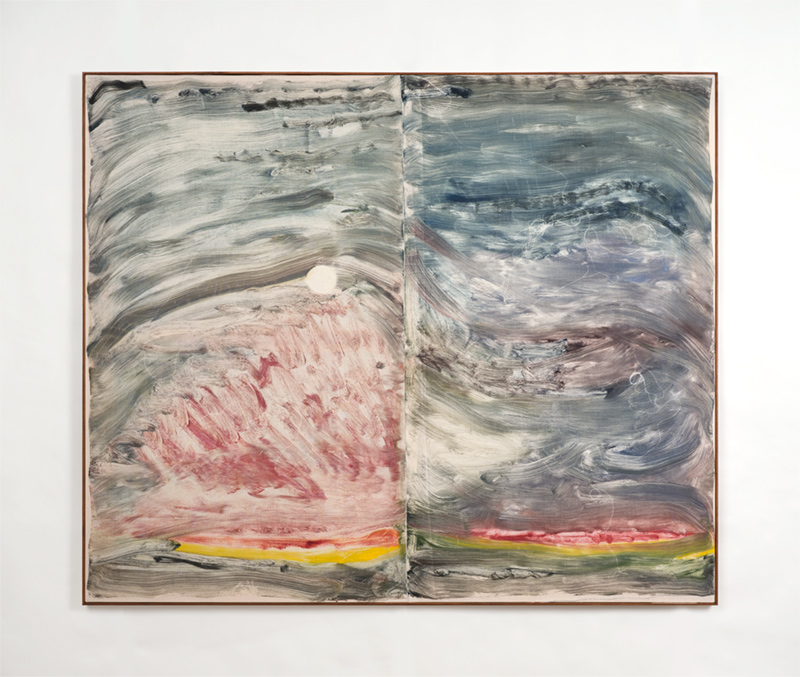

Aimée Parrott, ‘Whitehawk Camp’, solo exhibition at Mackintosh Lane, London, 2022. Courtesy of Mackintosh Lane and the artist.

From an ecological perspective I think the ability to work collectively, to try to empathise, and think beyond individual needs is the only way we stand a chance of salvaging something at this late stage.

In terms of my mindset about making art and how it is received, I think the idea of trying to make work with a ‘message’ or control how it is seen is perhaps egotistical. I think every artwork is a collaborative enterprise between artist and audience, of course works are digested differently by each person. I don't want to be didactic about the way my work is read and I like the idea, to some extent, of letting go of something once it is out in the world, relinquishing ownership and letting it take on a life of its own. When I make I try to leave space for chance and submit to circumstance, to set up an environment for something to evolve and be responsive to materials. I think what Paul Becker said in your interview with him about making work that contains some life, but isn’t ‘about’ something hit the nail on the head for me.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Ever becoming body’, 2022, monotype, fabric dye, acrylic ink, thread on cotton with artist's frame, 110 x 130 cm.

Empathy and affect

Can you tell me about the place of empathy within your work? This word is used in the press release for your exhibition Gaia’s Kidney at Broadway Gallery. It made me consider the ways visual art can make us feel something without telling us how to feel, as Simon O’ Sullivan states in his text The Aesthetics of Affect: ‘you cannot read affects, you can only experience them.’ What might empathy mean to you and why is it important for your work to elicit it?

For me empathy suggests giving someone or something careful attention, one might try to empathise with a particular place, a person or with nature. I see it as an attempt to try to find an affinity with things, to approach one’s surroundings with a sensitivity and an openness, making these tentative connections with one’s environment, whilst acknowledging the gap between my experience and someone else’s. In trying to behave empathically where possible, I suppose I hope some of that sensibility is suggested within the work.

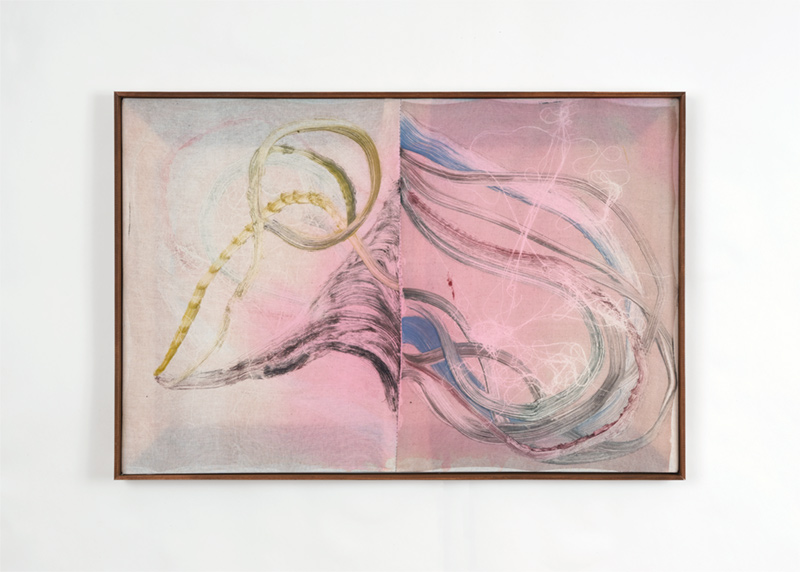

Aimée Parrott, ‘Heavenly Body’, 2020, monotype, thread, ink on calico, 100 x 130 cm (left). ‘Radiate’, 2020, tulle, thread, ink on calico, 100 x 130 cm (right).

By sea

I’ve been wondering if location has influenced your work, and particularly coastal geography and the presence of the sea? I think Whitehawk Camp is the name of a campsite near Brighton and you undertook your BA in Falmouth, a coastal town in Cornwall.

Whitehawk Camp is an important Neolithic site in east Brighton, it was discovered when new housing was being built in the 1920’s and 30’s. I decided to name my recent solo show after this site having just moved back to Brighton (where I grew up) after 10 years in London and found myself rediscovering a place which I had fixed my opinion of in my teens. When I was growing up Whitehawk had a reputation for being quite rough, having high levels of poverty and crime despite being part of Brighton, a relatively affluent city. Discovering its ancient prominence helped me see it anew in a wider context. I thought the name Whitehawk sounded quite romantic without context, however with knowledge of its recent and ancient history it’s a more loaded title.

Location absolutely has an influence on my work. Having felt claustrophobically landlocked for ten years I’ve realised that growing up and studying by the coast has given me a particular perspective. I think the sea has always comforted me, it’s scale and its changeability make me feel small and sort of connected to something larger and beyond my control. Seeing oneself in relation to elemental forces, ancient civilizations, deep time, even rock formation somehow makes me feel more at peace with my insignificance, more willing to go with the flow of inevitable change and accept the chaos of it all.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Chalk bed’, 2021, monotype on cotton with thread, artist’s frame, 125 x 110 cm.

Hawkes' book, A land, resonated with me because she so actively and imaginatively links the landscape to individual consciousness and highlights how bound and rooted we are to the earth in a way that seemed to collapse the 70 year gap between now and when she wrote it. Though the paintings aren’t necessarily illustrative of this, the way they are made perhaps reflects something of this state of mind.

I made the paintings for Whitehawk Camp when I was experiencing a lot of change. I think sitting atop an ancient hill and picturing the very slow-paced geological change involved in its evolution pared with the rapid and slightly unnerving change I was experiencing in pregnancy, disorientated me in a way I found interesting. I enjoyed the imaginative leap it took to think of two very different time scales running alongside one another. This duality is a quality I try to bring to my paintings. I often use forms that play with scale and time - a shell, mouth, cell, planet, hole - stretch between the micro and macro suggesting multiple forms at once but rarely settling on a namable, stable thing. I hope that this then keeps the eye and brain in flux whilst pointing towards ideas of growth, creation and change.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Under the skin’, 2022, ink, thread, monotype on cotton, artist’s frame, 170 x 140 cm.

The Domestic

You mentioned that your current studio is at home. Has working at home influenced your practice? Your home studio made me consider the domestic associations of some your processes (embroidery, sewing, flower pressing…) and historically, the gendered nature of these processes. Do these associations interest you?

Up until a year ago my studio was in a large, industrial space in east London - it is now at home for practical reasons - I have baby twins - but I have long found inspiration in processes with domestic connotations. I’m not so interested in the gendered nature of these processes, but I think female artists of the past had to find pragmatic ways of being creative (in that the objects they made often had to be practical too) and perhaps this limitation bred more interesting, hybrid creations. The Gee’s Bend quilters for example were making these spellbinding, imaginative, pragmatic and often collectively produced works in the mid-20th century that were overlooked in favour of abstract expressionism - a movement that, though it produced some fantastic works, was really weighed down by male ego and angst.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Spring’, 2020, monotype on calico, acrylic, wool, polymer clay, thread, pine, 32 x 42 cm.

I think it is wonderful that old, patriarchal hierarchies in fine art are in some ways being broken down, and art history is gradually being expanded and rewritten. For me, inspiration can come from anywhere, I want my practice to be porous thing. Being in a domestic space means you have to let life in. Whilst I enjoy the ‘purity’ of painting, at times I like to extend painterly concerns on to practical objects. I recently made a series of lamps that I found as challenging and engaging as making a straightforward painting.

I like the idea of practical objects made strange or elevated, hybrids that sit between artwork and appliance - I think that is why places like Charleston House are so fetishised - it’s really appealing to see a domestic space where nearly every object has a sense of the artist’s trace on it, everything considered and playfully interacting with one another.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Chameleon lamp 1’, 2021. Lampshade: length: 24cm, diameter: 33cm. Base: length: 30cm, diameter: 8cm. Total height: 52 cm.

A day in the life

In practical terms what might a typical day in the studio be like?

At the moment I’m not doing much active making - because of the babies - instead I have hung unfinished paintings all over the house so that I can have longer, drowsier looks at them and make decisions about them more slowly. I have always made compulsively and relentlessly so I’m interested in what this forced slowing down will yield.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Low Pressure’, 2022, monotype and fabric dye on cotton, 110 x 130 cm.

Magic

Printmaking can be magical in the sense of action and chance coalescing into something unexpected; an apparition we can summon but not totally control. How do you know when something is working aesthetically and how much do you allow yourself to be out of control?

As a starting point I find a lack of control in the process so important and the monotype for me uniquely enables the combination of direct gesture, chance and transformation to coalesce. In beginning a painting I like to imagine just enabling it to arrive, being receptive to materials and circumstance almost like a conduit. Once this base is established I feel I have something to react to, to coerce or to breakdown, so I suppose it is a mix of relinquishing control then trying to reestablish it. Working in this way means it is massively important to be able to edit, for every 10 paintings I make 1 will make it out into the world.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Red eye’, 2021, monotype and ink on 300 gsm Somerset satin, 42 x 58 cm.

Evolution

There has been an evolution in your work away from more graphic representations of the figure (your solo presentation at Breese Little, 2016) towards more enigmatic and ambiguous image making, or, as you say, a move away from the ‘voyeuristic gaze’ of figuration towards a bodily or sensuous gaze, almost like seeing from the gut. How would you chart this evolution in your practice and is the idea of a ‘gaze’ still relevant to your paintings?

I think the more graphic figurative work in the Breese Little show was a reaction to my time at the Royal Academy. I found it very hard to talk about my work whilst I was there, the performative aspect of group crits paralysed me so I think I made work that was quite slight and opaque in response. In leaving the RA I felt this overwhelming freedom to make something more bombastic and direct.

Ideally, I’d like there to be room for both inner, visceral and exterior points of view to be expressed within the work. To be able to chart multiple sensations and perceptions held at once, a reflection of how it is to be in the world, how messily our physical experiences and mental understanding of things collide. Sometimes figuration still makes its way into artworks but on the whole I find it a bit restrictive, the questions seem to change with figurative representation. A namable object or depiction seems to suggest stasis or to invite a linear narrative and I prefer to think about forms in a more fragmentary, fleeting way, in motion, either in the process of becoming or dissolving.

Aimée Parrott, ‘Banner’, 2016, latex, linen, thread, steel, wood, 245 x 166 cm .

Frame and Seam

The framing of your work gives something soft a structure; drawing fragments, processes or material layers together into conclusion. I love the way seams interact with this geometric stretching, offering a sense of disobedience or materiality beyond the painterly image. How important is editing and framing to your work? Does stretching/framing always happen at the end (like in printmaking) or is it a more integral part of your image making process (like in painting)?

I see the frame as an integral part of both the art work itself and a way of finalising or solidifying it. The rigidity of the wood emphasises the softness of the fabric surface, they activate one another. I’ve been lucky enough to collaborate with some amazingly creative framers (FRAME London) who have helped me to push and develop this aspect of my practice.

In terms of stretching, until the work is framed it is very mobile and fluid. I never prime my works so that the fabric can be taken on and off the stretcher multiple times. For me this rough treatment, a sort of deflation, means that the painting becomes rag-like, marks get warped or creased and this helps me to be less precious and mannered when I’m working. My interest in painting stems from its potential duality - the complexity of being at once an image and an object. In working with unprimed surfaces I have intentionally tried to hold the viewer on the surface, attempting to reinforce its materiality, the weave of the fabric. It’s malleability and fragility feature as prominently as the marks upon it. The subtle relief of the seamed pieces is barely visible when the work is condensed into an image, only becoming apparent when face to face with the work, in this way I hope to complicate and slow the reading of the paintings.

Aimée Parrott, ‘2.2.22’, 2021, monotype and fabric dye on cotton, artist’s frame, 40 x 60 cm.

Future

What are you currently working on or thinking about?

I’m working towards my first solo exhibition with Parafin Gallery in 2023 and wondering how sleep deprivation will change my paintings!

Aimée Parrott, ‘Thunderstone’, 2020, monotype on calico, acrylic, wool, thread, pine, 32 x 42 cm.

Friends

Finally, which artists do you look to and appreciate from history and our present moment?

I was lucky enough to study with some amazing artists during my time at the Royal Academy; Alice Theobald who just had a show at South London Gallery, Julie Born Schwartz and Kira Freije, who just put together an amazing exhibition of her sculptures at The Approach, to name but a few. It is so gratifying seeing them go from strength to strength, their practices developing and deepening over the years.

I took part in the Artist Support Pledge during the pandemic and it enabled me to support existing artist friends, discover new ones and build a small collection of my own. I now live with works by Alex Crocker, Pam Evelyn, Linda Hemmersbach, Tom Owen, Tom Worsford, Daniel Lipp and more. Living with these works and looking at them every day is so enriching and a great reminder that the tangible objects are so much more gratifying and nuanced in person than images on Instagram!

I’m lucky enough to be exhibiting alongside some of my favourite historical artists at the moment in an exhibition at Pallant House about the Sussex landscape; J.M.W Turner, William Nicholson, Vanessa Bell, Duncan Grant, Ivon Hitchens, Eric Ravilious and Edward Burra all feature, it’s a dream to have my work sit beside theirs.

If I could pick one artist that I come back to over and over again it would probably be William Blake. I love the peculiarity of his work, its individuality, its quiet drama and the way he connects his art so wholeheartedly and unashamedly to the spiritual in such a personal way. I think he was a true visionary.