Chroma

Angelina, your colour palette is very distinctive; lots of pistachios, peaches, browns and blue greys. They make your paintings instantly recognizable as yours; as belonging to the aesthetic world you have created. How did you come to develop this palette and what associations does it carry for you?

Colour is one of the most important elements of my work. I have Synaesthesia and everything has colour (numbers, letters, names etc.) so I think in colour and I feel as though I absorb colour constantly from different places, films, cartoons, objects, packaging and food. If the colours don’t feel right in the paintings, if they don’t cause a physical reaction in me then I change them. I often just spend hours adjusting the colours in a painting until something switches on and they come to life. I don’t know if other people get the same feeling from the colour palettes that I use. I am also fascinated with how colours can belong to the present and then become consigned to history. Television does that. If you watch something from 10 years ago the colours are definitely from the past. You can locate things very specifically in time through colour, especially on screen. Also, I grew up at a time when we still had a black and white TV so colour on screen was special and I noticed it, all the nuances in the different things that I watched, the difference between colours in a Hanna Barbera or a Loony Tunes cartoon. I could tell instantly from the colour palettes if I was going to like the cartoon. I used it to identify things, make decisions based on colour. I think that I still do subconsciously.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Glade’, 2019, oil on canvas, 140 x 140 cm.

Landscape

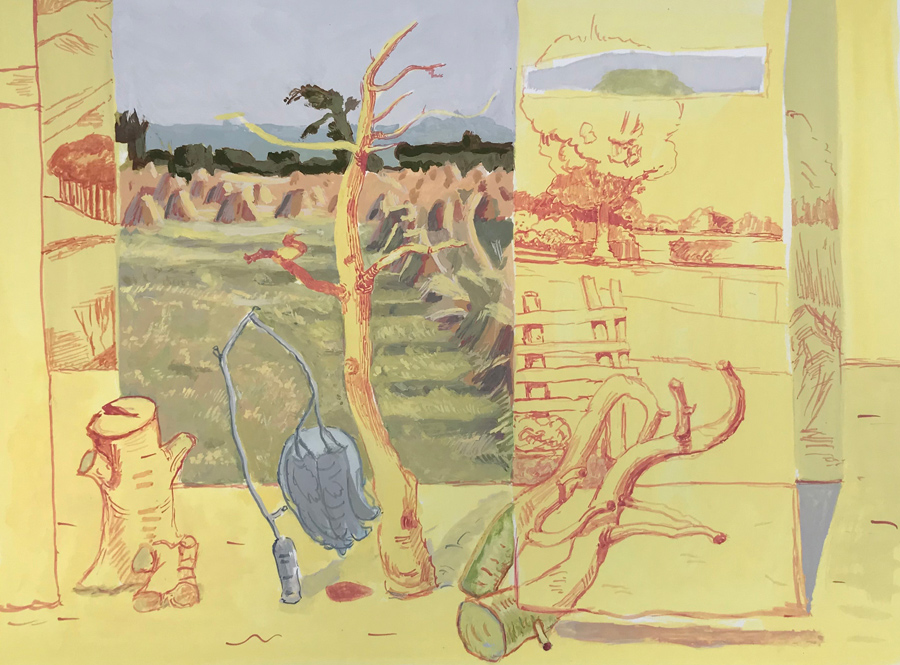

My initial reading of your ‘landscape’ paintings is that they deal with the staging of nature and how our ideas of what looks natural may actually be the product of landscaping, colonialization and myth. Do you see yourself as working within the historical genre of Landscape Painting, albeit in a contemporary way?

I am aware of the history of English Landscape painting; Gainsborough, Paul and John Nash, Graham Sutherland, Samuel Palmer are all painters that I have been interested in. Gainsborough’s landscapes have the feeling of being staged, and his showbox at the V&A in particular resonates in the way that he creates an interior version of a landscape and a contained space for the imagination (like TV - the ‘box’). I didn’t start painting landscapes until about 8 years ago. I was painting objects; slide viewers, packaging, books with photographs of Alpine landscapes in them (my grandmother was Swiss) collected from second hand book shops. I started to bring landscape into the studio, almost as still life.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Pink Summit ‘, 2017, oil on canvas, 154 x 122 cm.

But then I started thinking about how my sense of identity is located in the landscape, growing up in a village and about what I felt about rural England, about the tension between the attitudes of conservative middle England and the working life of a village, the reality of rural life for lots of people. That definitely connects to history and the way that rural life is and has been organised. The hierarchies that are still present and visible. My dad used to take me to the Pytchley Hunt meet on the village square. I remember the stubble being burned at the end of the summer. I always felt that the edge of the village was where the countryside began, that you could see it but couldn’t really get in to it. It belonged to farmers and was inaccessible. I re-read Evelyn Waugh during lockdown and was struck with the nostalgia for a past England and the problematic language and attitudes. I hadn’t noticed that when I read them as a teenager. I wanted to think about that in the paintings. I used the paintings to think about how landscape is an idea, and one that has changed through history. Not just in paintings, but in film, illustration and advertising. I read a really interesting book ‘British Rural Landscapes on Film’ which explores the way that landscape has been used in film as a metaphor for different emotional and psychological states. It made me much more aware of the potential of landscape to be manipulated and how I could fabricate a space that felt familiar, in which I could play out all these different ideas.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Haymakers’, 2021, gouache on paper, 21 x 29 cm.

The Lark Ascending

When reading more widely about your work I started to think about British pastoral aesthetics – such as the work of William Morris and his friend the composer, Vaughn Williams. How do you feel about pastoral myths or representations of pre-industrial England? Do you long for Albion or find the celebration of our green and pleasant land suspect? Perhaps your show ‘Coming up for Air’ touches on this sense of longing for a lost idyll?

The tension that you have identified in those questions, between a longing and a deep mistrust of the way that we are fed a pastoral idyll is something that I acknowledge. I know that I have been manipulated, that film and graphic adverts have presented this England as somewhere that doesn’t really exist. But I also feel a longing for something. When I saw Hockney’s painting of ‘Hawthorn Blossom’, I knew exactly where it was in my own past. But nostalgia is a cover, a distraction and behind the facade is a much more problematic history. I can’t avoid that working with the landscape.

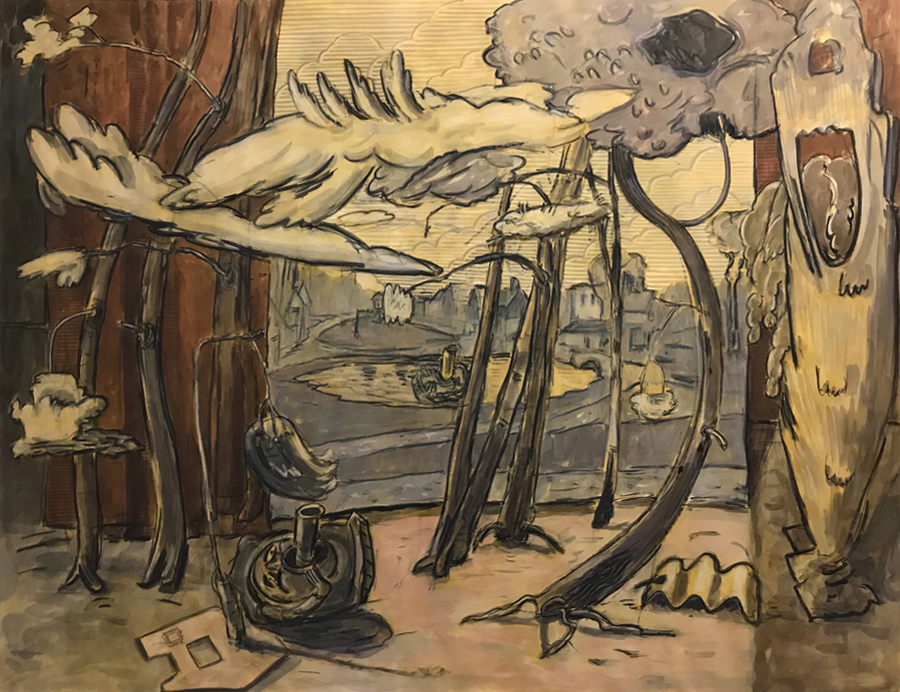

‘Coming up for Air’ seemed to form itself as a body of work. I didn’t set out to create those works, they came through a gradual understanding on my part as I painted them. I began searching for images of Elm trees because I was aware that the Elm died out during my lifetime and it occurred to me that it had disappeared from film and it was the most recognizable tree in all those historical English landscape paintings with its figure of eight silhouette. I have used it as an emblem, a motif that stands in for loss. That led me to looking at all sorts of different depictions of landscape; archival film footage of harvests, old books, the books from my parents’ modest bookshelves, shell guides, local history booklets. But sometimes things just surface from somewhere in my own past, from remembered films that depict England almost as pantomime.

Angelina May Davis, ‘If only it could stay like this’, 2021, oil on canvas, 154 x 240 cm.

‘Greensleeves with Fixed Penalty Notice’ started as a drawing of some trees in Yorkshire standing in shallow water, and became a lush green landscape, with exuberant trees and a banner of golden leaves, carved in paint; a heady mix of English landscape and decorative deco, summoning up a past that has never existed. Concealed within the folds a Fixed Penalty Notice, discarded casually but working its way across the painting, as an anxious reminder of the small struggles of everyday life. I use colour to manipulate the viewer and create an emotional response, lull them into a sense of that idyll that you mention and then disrupt and fracture the tranquillity, sometimes in a sinister way other times through humour.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Greensleeves with Fixed Penalty Notice’, 2022, oil on canvas 154 x 137 cm.

Chelmsley Wood

I was thrilled to discover the brilliant text that painter Hannah Murgatroyd wrote for your show at Oxmarket Contemporary. Amongst other things it opens up your work to a nuanced discussion of class and place; through mention of interior decor and the enclosure act. You also mentioned ‘being a Brummie’ to me. This clash of urban and rural is to be found in sites such as Chelmsley Wood in Solihull; once the largest estate in Europe, it was built on ancient wood land. I am curious how Birmingham, and potentially a sense of class histories, informs your work.

Despite what we are told about how we live in a classless society, the layers of inequality in society still seem to be rooted in the hierarchies of history. I feel affronted by the way our current leaders appear to be plunging us back into a past that we are told to be grateful for and be filled with a sense of national pride. In ‘Bowing and Scraping’ I was mocking the idea of our own foolish nostalgia and of ‘knowing your place’. My parents moved from Birmingham, from working class families, to a village. They had aspirations. Villages seem to magnify those things. And there are signs everywhere, the local history society, the amateur dramatic group. Moving to a city when I went to art college in Coventry in the 80’s was a culture shock. I was terribly homesick and missed everything that I had become bored of.

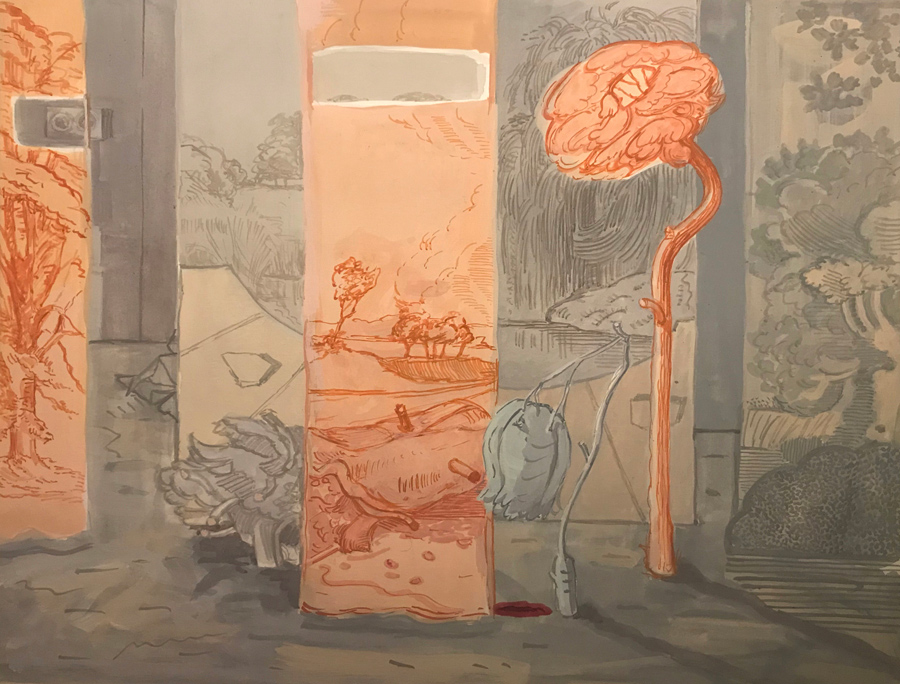

Angelina May Davis, ‘Coming up for Air’, 2021, ink and gouache on paper, 152 x 120 cm.

Now I live in Bournville in Birmingham in what is essentially a village. It has a village green, a cricket pitch, boating lake etc. My parents worked and met at Cadbury so I have come full circle. And the artificiality of Bournville isn’t lost on me either. It’s a constructed world, frozen in time and like all those other model villages it has moved from being a place for workers to a highly desirable, and in parts exclusive, estate beyond the means of the average worker.

Birmingham grew very large very quickly during the industrial revolution and there is evidence everywhere of the rural past just beneath the surface. I live on a lane with ancient oak trees and what was a farm building at the end of the road. You can drive through parts of Birmingham and suddenly be in what feels like the countryside with fields to one side. It’s quite odd but that connection to rural in an urban setting is probably what has kept me here for so long.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Staged’, 2022, ink and gouache on paper, 152 x 120 cm.

All the world’s a stage

I love the theatrical elements of your work; the depiction of landscape as flimsy backdrop, stage curtains, props. It makes me think about the connections between drama and painting via the tableau or ideas of artifice, narrative or allegory. How and why did you begin incorporating theatrical motifs into your work? Is it something to do with evoking pathos, or alternatively with creating the space for critical distance?

I think in the first instance it has to do with a long-standing obsession with making stuff, creating sets for puppet shows as a child, props for games or fake cheque books. I also had a fascination when I was younger with the furniture shops that my parents took me to and the fake books on the shelves that created the sense that you were actually in a room; props. I like creating the world in which I can play out dramas or discover them as I paint. Staging things, suspending disbelief, allows you to think about things, like history, and where your ideas and values have formed and what you feel about those things. I try to use painting to explore and to question. And as I anthropomorphize everything and see character and drama in everyday objects and the domestic it’s easy to make that step in your work. It does allow for a distance. You can watch it unfold, narrate it or be the spectator as you paint. You can sort of be everywhere in it. And curtains are great because you can conceal things behind them but still see something sticking out underneath. There is humour in that. I don’t think I consciously decided to paint theatre sets, but I love dramatic lighting and the dimension of things when they cast shadows. So, it naturally creates a kind of artifice and an unnatural atmosphere, which you can then play with and manipulate. I also love how a set reveals more than one world, what is just out of view, the gaps in the curtains, raising the question as to what is real. So, in terms of the subjects that I am exploring it feels right that nothing is fixed and there are edges everywhere. I am interested in edges both in relation to the spaces that I paint, the locations that I visit and in the way that edges can suggest otherness.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Fallen at the Pond’, 2021, gouache on paper, 21 x 29 cm.

Drawing

On your Instagram account you share beautiful drawings, perhaps made during walks (through Mosely Bog) or from images of landscape. Where is the place for drawing in your practice and how does it inform or feed your paintings?

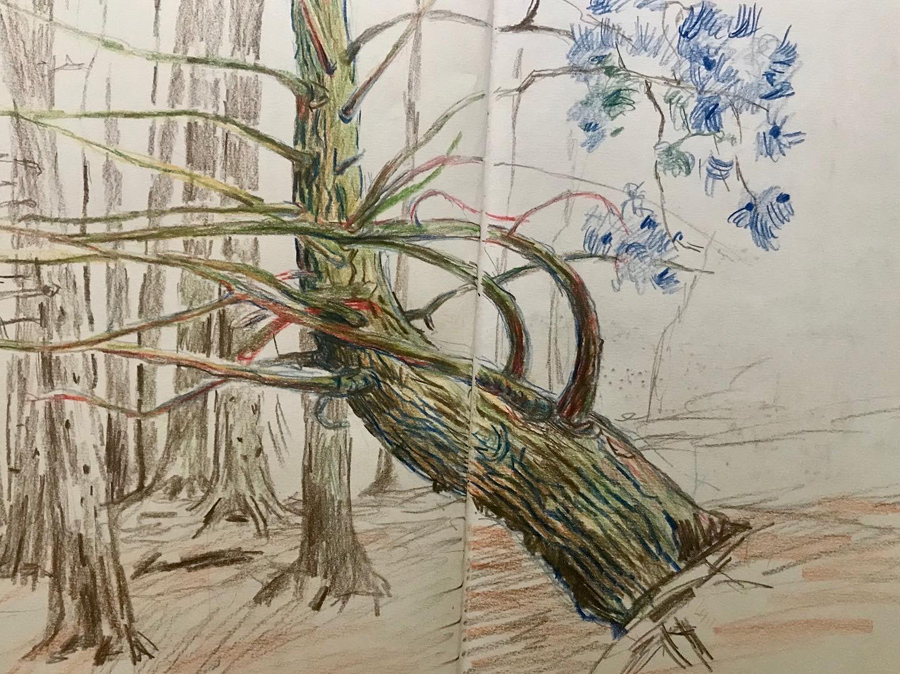

Drawing is and has always been at the centre of what I do. Whether I draw from looking at life or from memory or use it to invent. Drawing is about searching for a language to think about experience. If I sit in the landscape and draw I become absorbed by the feeling of the place in a way that is much more intense than just sitting and looking. When I paint, drawing comes into that process. I can’t work from photographs. The painting ‘Coming up for Air’ literally materialised in my sketchbook when I was drawing at the Lickey Hills. As soon as I had made the drawing of the group of trees I could imagine the painting and the other elements that would be in it. I painted directly from the memory of that and the drawing but staged the rest of the image. I want the paintings to be alive and drawing gives me a way of painting that is very active and transformative. It is a process that I carry into the paintings. I try to go into a painting with an image that has come from drawing and use the memory of that to manifest something that I can then develop through painting it.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Lickey Hills’, 2021, coloured pencil crayon, from sketchbook.

Journey

You’ve been making work for a long time and the skill and confidence of your experience really comes through in your current painting. What kind of work were you making on your BA at Coventry Lanchester Poly in the late 80’s? What kind of journey has your practice been on and are there any threads that run through it over time?

When I went for my interview for a Foundation Course at Nene College, I took a painting that I had made of a stately home. The lecturers laughed at it and I knew that it was terrible too because I had no idea how to make a painting. I don’t think that I made a good painting until just after my degree. At art college I mainly painted from interior spaces and from my experiences at the time. I developed a language in painting to map and record information and the work was autobiographical and full of narrative. It was just after that when I was in studios in the Custard Factory that I began to pare things down to essential forms and refine my use of colour, taking colour palettes from cartoons. I was in an exhibition ‘The Secret Life of Objects’ at Ikon Gallery and the work was very animated. I used comic book humour and commented on the domestic and my feelings about being female. I used objects, found images and illustrations to construct a personal world. So, in many ways I haven’t travelled that far from where I was 25 years ago. I had my older daughter just after I began my MA at UCE and the anxiety of motherhood surfaced in my work. If I look back at what I have been painting over the years I would say that collecting objects and using them as props or characters and allowing relationships to form and narratives to unfold has been a constant thread in my work as has a love affair with oil paint! I love the stuff. And I am as hooked on the stuff of paint as I was back then.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Pile up’, 1996, oil on canvas, 122 x 154 cm.

Process

What is your process of developing a painting? Do you work from collages or studio set ups? Do you plan compositions or is there room for improvising?

I develop paintings in different ways. Sometimes I just make a large canvas, stretch it, size it, prime it and in the process of making the support which is quite time consuming, I start to imagine what will be on it. And I start from an idea and try and tease it into being. Other times I will have a drawing made in situ that sparks something. I make small gouache paintings, collages, ink drawings, all as a starting point for painting. I used to build sets and paint from them directly and I did this for a number of years but I am more interested in what comes from not having something in front of you, from letting paintings form themselves. Sometimes I will put something in front of me so that I can understand the way that it sits in the space or the way that the light works. But I am conscious always that paint transforms things and therefore each time you mix a colour or choose a brush to make a particular mark I think you have to transform what you are looking at in some way. It’s not enough just to copy things. I want to surprise myself in the choices that I make. I want to find out what the painting is by doing it rather than already knowing what it’s going to look like, even if the thing is in front of me.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Harvest’, 2022, oil on canvas, 100 x 100 cm.

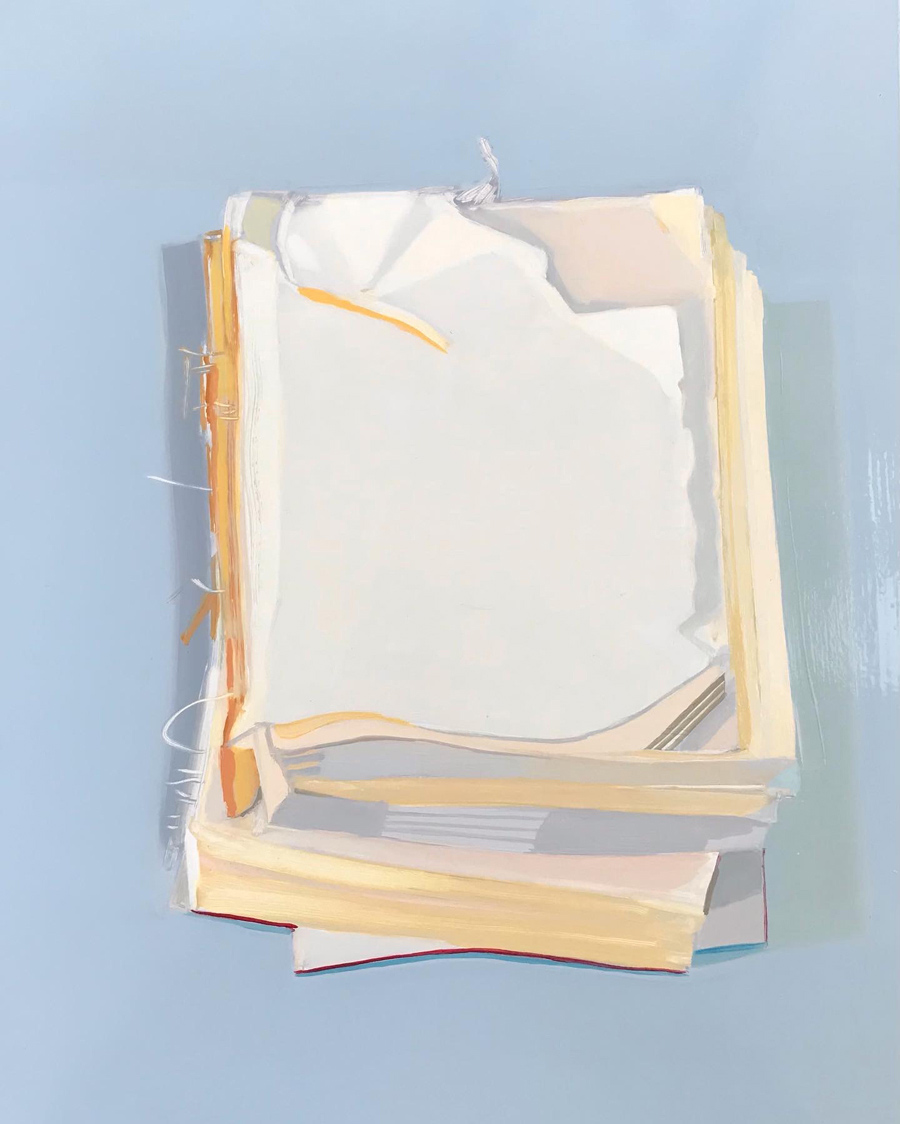

Book

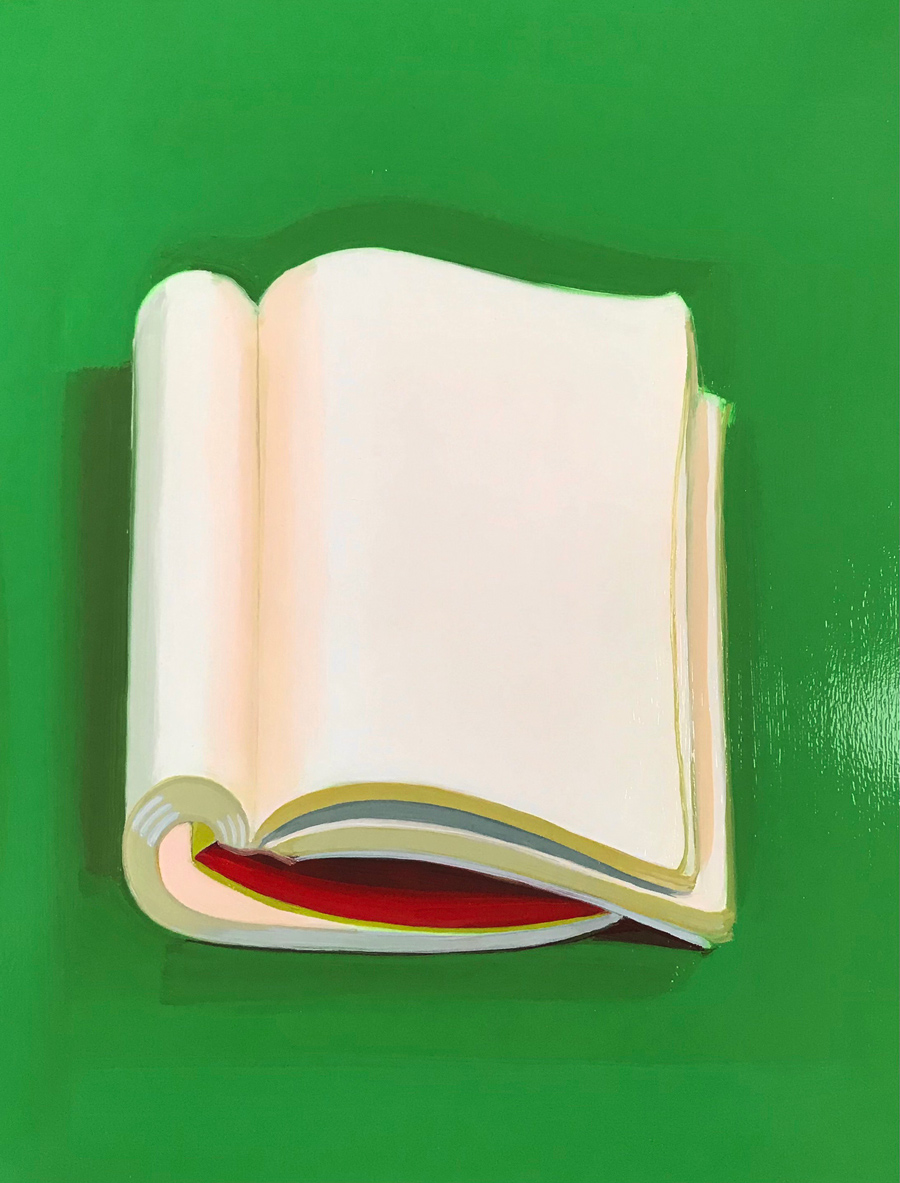

Your new book paintings are very compelling; distilling your interest in figure and ground, still-life and colour into focused works. They feel composed, confident, luscious – perhaps like a Wayne Thiebaud painting in terms of their focus and luminescence. Where did this body of work come from?

It goes back to the idea of the object. I started that series almost by accident. I was painting all day in the studio and nothing was going anywhere and in the last couple of hours I just decided to paint a green book from my imagination and then paint a small image of a castle on the front cover. The castle came from a 1950’s school textbook that included chapters on English History, the Empire. Really jaw dropping stuff, actually. The book that I painted felt like a book that could be on those shelves in my parents’ house. Or a book from one of the houses in the backdrop of ‘Coming up for Air’. The castle is a loaded image. From medieval England to Disney. And books themselves are too. But they are simple objects that are great to paint in an almost abstract way. Just slabs of colour. I like that books could be seen as relics, something that is being superseded, but actually at the same time we keep returning to material things. We can’t let go of them even when they are obsolete. We collect them and want to bring them back to life. And historically books have agitated, rallied, spread ideas, propped up tables, been used to signify status, education, they’ve been burned, seen as dangerous, frivolous. People write in them, carry them around and re-read them until they begin to fall apart. There is so much material to explore I have only just got started.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Dummy 2’, 2022, oil on cradled board, 28 x 35.5 cm.

Future

What are your intentions for future works? Is there one element of your work you’d like to mine or push further?

At the moment I am interested in the books and where they might go, I keep finding new forms of books (folders, diaries, textbooks etc.) and I have started to make much larger boards, larger than life. I wanted to make them monumental. There is something about the clarity of working with a single object. But then I also have a book of ‘English Villages and Hamlets’ from 1934 that I have used to draw up a tour of England which I intend to begin this summer. I wanted to visit a selection of the most picturesque villages from that book and to draw intensively and research them to see where that might take me next. I don’t feel that I am finished with the landscapes, and I have pushed that body of work further and for longer than anything else that I have produced, so I’m curious to see where that might take me next.

Angelina May Davis, ‘Restoration’, 2020, oil on canvas, 160 x 140 cm.

Friends

Finally, which artists do you look to and appreciate from history and our present moment?

I have a great long list. But there are some things that I have seen which have really stayed with me;

Frances Bacon at the Tate in 1985, the first exhibition of painting that I saw and which blew my mind and made me realise that painting wasn’t a watercolour of a windmill in Norfolk!

Phillip Guston at RA in 2004 I was already a big fan but being in a room full of Guston paintings was like standing in a wind tunnel.

Joseph Beuys' ‘Plight’ at Anthony D’Offay around 1985: A felt lined installation that sucked all the sound out of the world and was the first really immersive experience that I had with an artwork.

Graham Sutherland’s altar piece in Coventry Cathedral. All that green! Paul Nash, Samuel Palmer and John Piper for the surreal the visionary and theatre in their work.

Elizabeth Price’s films at the Whitworth a couple of years ago. I couldn’t tear myself away. I particularly loved the stillness and opulence of ‘In the House of Mr X’.

Film is a language that I am very familiar with and there are lots of filmmakers and films who I would put in the list including Alfred Hitchcock’s 'Rope', Ken Loach’s 'Kes' for the slowness and space that allows you time to really process what you are watching. I enjoy slow films!

It was great to go to a big mixed painting show recently in ‘Mixing It Up‘ at the Hayward and Daniel Sinsel’s sensuous tromp l’oeil paintings really grabbed my attention with their ambiguity and humour. And Louise Giovanelli’s curtains stopped me in my tracks.

And finally, 'British Rural Landscapes on Film' Edited by Paul Newland.