Words and Pictures

Paul, I’d like to begin by asking you about the relationship between your painting and your writing. How do you divide your attention between these different modes of making? How do they inform or trouble each other?

That ‘relationship between the two’ is a pretty fundamental question I have struggled with a great deal, so yes, they trouble each other a lot. The answer is not really that simple (and why should it be?) but what I have learned is that the two separate aspects do share certain concerns. In painting these can emerge or declare themselves more naturally, instinctively, and more commonly via accident, mistake, catastrophic failure, lack of skill, compromise; basically, via the incredibly generous nature of oil paint. In my writing, I have to be much clearer with myself in the process, about what it is I am trying to move towards. The concerns I am talking about lie in finding ways for the work itself to exist, to have a kind of autonomous existence, to have depth and vibrancy; to contain some life but to not necessarily be about anything and to not descend into meaning. In my writing, as I say, I have to work in a more strategic way (editing, cutting & pasting) but I am still looking for similar things to happen, I think. That is: not knowing and the excitement, the alchemy of producing something from nothing, with nothing. It used to worry me when people asked me what I did as an artist and I couldn’t really explain. Now I think it might be a positive.

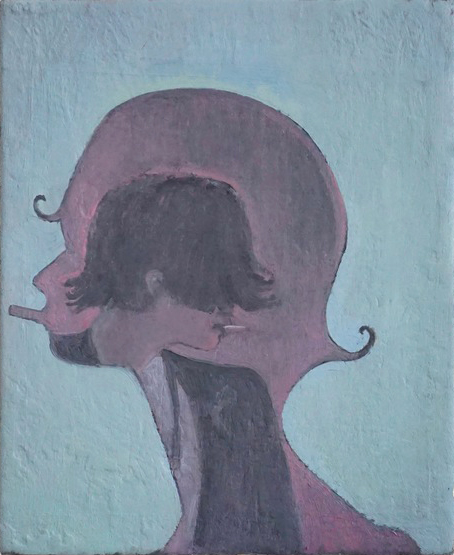

Paul Becker, 'Reader, Smoking', 2019, oil on linen, 17 x 11 cm, (Private Collection).

Alphabet

Following on from this, can you tell us a little about your ‘Alphabet’ works? How did this series begin and what draws you to the alphabetical and typographic?

I think any influence of the typographic comes from my wife, Nadia Hebson, who has been using that sort of imagery for a long time. Her work is a huge influence on me and on my thinking. Originally, I had wanted to produce an alphabetical ‘primer’ for my twin boys to put up in their room but the images were too oblique for that. And they kept coming.

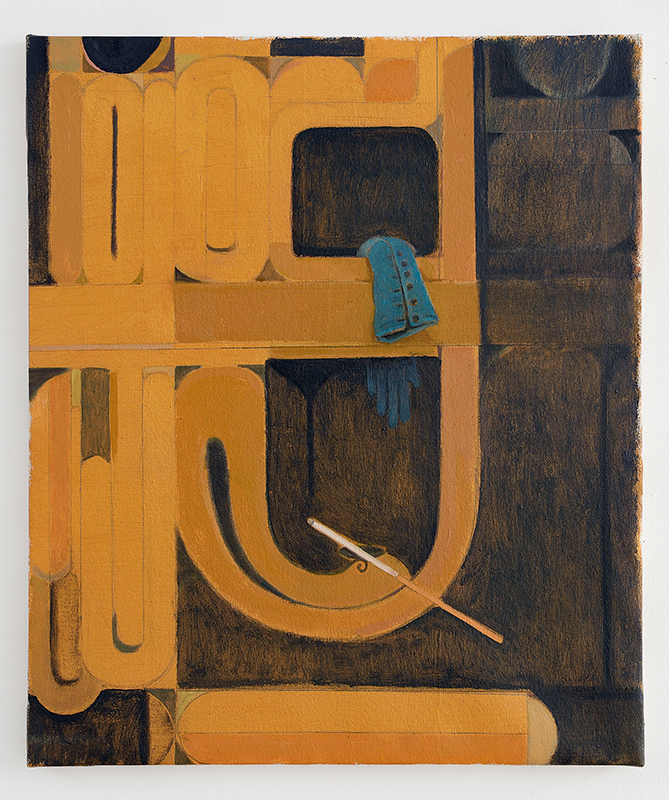

Paul Becker, 'P.S.', 2020, oil on canvas, 73 x 81 cm.

Visual Language

Within your paintings certain formal strategies reappear: images within images; Art Nouveau curves dancing between figuration and abstraction. The relationship between figure and ground is often ambiguous. Do you strive for a sense of perceptual ambiguity when painting?

I think the grounds are often ambiguous because they have usually changed so much since the painting started. The surfaces are highly fought over. Lost paintings and pentimenti, re-emerging. So, I am looking for them to somehow hold the figure and somehow exist as an atmosphere as much as a space. Do you know what I mean? I am not really interested in using a traditional pictorial space or in any sense, perspective. I don’t really hold with the rules of perspective. I am much more interested in painters who make their own rules in terms of the spaces images inhabit. Charlotte Salomon, Giotto, Frida Kahlo. Because my paintings are not really to do with perceived reality, I feel I have more leeway. They still have to operate but each in their own way, with autonomy. It is not so much a perceptual ambiguity but an emotional one and the formal aspects of painting are allied to that, they are not cold and lifeless.

Paul Becker, 'Untitled', 2016, oil on linen, 91 x 91 cm.

I am really interested in figuration and always have been but abstraction and decorative painting interest and excite me too. I was taught painting at a very male dominated time in the ‘80’s when abstraction was perceived as painting’s ultimate destiny. There were so many things one couldn’t do as a painter. It was like a litany: The Subjective, The Decorative, The Emotional, The Humorous, The Illustrative, The Erotic, The Cathartic. Etc. to say nothing of work that was coming from a non-western standpoint. I mean, painters still worked in these ways, they just couldn’t get the work seen or shown. Luckily things have changed a great deal.

Paul Becker, 'The Bow', 2019, oil on linen, 63 x 63 cm.

Mute

One of the most seductive things about your visual works are their muted colour palettes which mine the ambiguous values of tertiary colours. There are various browns (umber, ochre, sienna) that nudge against turquoises and purples. ‘Painter Portal', 2015 is a great example of indeterminate colour values – where lilac may also be burgundy. Can you tell us more about your palette and your relationship to colour?

Bold, primary colour is lovely, of course but it is really not a short cut to any realm of deep emotion. My colours are subtle, nuanced, ambiguous because the paintings are meant to be. Things are never immediate. Subfusc colour carries the content further. The way the paintings are made, like reverse archaeology, with so many previous failures being scraped down and re-revealed, the colours become delicately layered and ghost through. I am looking for these touchstones all the time. I want them to be beautiful. My first understanding of colour came via an astonishing foundation at Grimsby School of Art. The tutors were ex- Slade so there was a lot of talk about Whistler’s ‘gravy’ and ‘middle tone grounds’. My sister used to say all my paintings back then looked like German mustard. The painters I return to are the most nuanced in terms of colour and tone. My first love was Gwen John.

Paul Becker, 'Painter Portal', oil on canvas, 30 x 40 cm.

Ennui

Your images feel part of the same aesthetic world like stills from films made by the same director. Exquisite cats, long fringes, faces resting in hands, berets and endless smoking. It reminds me of what I thought French culture was like as a teenager: Godard; poetry; being cool; a dual-text copy of ‘La Nausée’ poking out of a greatcoat pocket. A kind of exotic, luxury boredom that one can only ever aspire towards. How do you feel about this reading? Can you tell me more about these recurring subjects or motifs?

The ‘aesthetic world’ you talk about has lots of crisscrossing references and contradictions for me. My true period is definitely the fin de siècle and a lot of the figures seem to come from or inhabit some exotic, wealthy, demi-monde of impossible pleasure. Those images and that atmosphere seem really joyful to me. ‘Perverse’ still has validity as an adjective only if it is wholly positive and joyful. But there is also something in the paintings relating to my own fears, fascinations and prejudices about English society and the iniquities of its class system. I think Beardsley had some of that going on too, don’t you think?

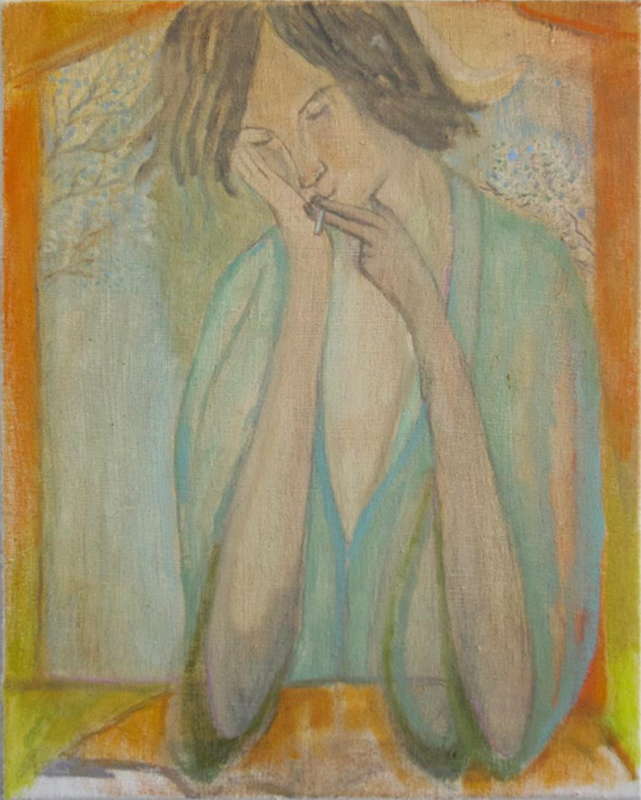

Smoking is something else. That feels more related to painting itself. I don’t smoke anymore but cigarettes are still beautiful to me and of course directly allied to contemplation. The connection to painting comes from it being purely a thinking space. At times, the thinking that painting produces can be more stimulating than the paintings themselves. There is a ‘state’ of painting, when one is looking at or making paintings, which exists in a space between daydreaming and reading and a cigarette is a kind of cipher for that. And I like the fluidity of cats, their indeterminacy.

Paul Becker, 'Le Chat', 2019. oil on canvas, 50 x 84 cm.

Salome

Can you tell me about your painting 'Skirt of ‘Toilet of Salome’', 2019? What is it about Beardsley or the character Salome that led you to create this work?

I have been interested in artworks containing artworks for many years. Occasionally, again I think from looking at Nadia’s work and the way she thinks about garmentry, artworks sometimes appear emblazoned on clothing in my work. This was an actual skirt we had seen someone ridiculously glamorous wearing at an opening in London. That it was Beardsley was very exciting as I have always loved him. He was someone whose work seemed to embody all that litany of things we were not permitted to do in the 80’s. He could do almost all of those things in one drawing.

Paul Becker, 'Skirt of 'Toilette of Salome'', 2019, oil on linen, 138 x 130 cm.

The Illusion of Certitude

The statement for your gallery, Vera Baxter (run collaboratively with Nadia Hebson) states ‘Most of us like to offer the world at least the illusion of certitude even if, when communing secretly with ourselves, we understand the amount of deceit this entails’. Can you tell us more about this idea of allusive personhood and how it may appear in your work?

I think it is more to do with Nadia and I wanting to allude to the possibility for an art space or gallery to exist that doesn’t operate in terms of explicating the work all the time but allows it more freedom to not make sense, to not function, to just BE. Like many artists, we both get confused by our interactions with an art world that thinks it needs clarification, codification, the continual laying out of meaning. There is this need to appear to know what one is doing when almost all of us clearly do not. My friend Giles Bailey used to say to our students when I taught at Newcastle, art is a really bad tool for clarification, for unequivocal explanation and is a much better tool for dealing with ambiguity, with mystery and with opacity. Nadia and I got really excited about how a space could function that facilitated all of those things for its artists. We haven’t had a chance to try (and probably fail) because of the pandemic and having twins but we will. We are pretty tenacious.

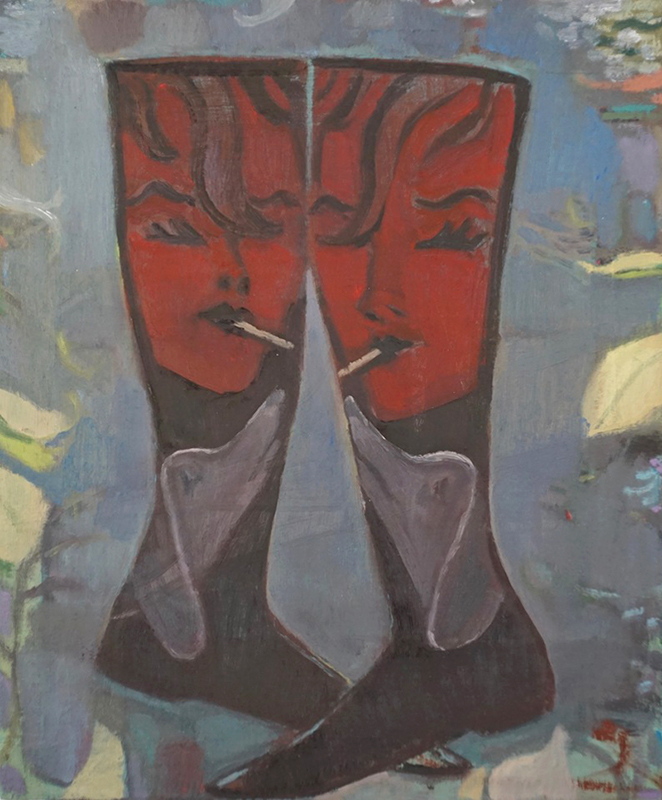

Paul Becker, 'Twin/Dog Boots',2019, oil on canvas, 44 x 37 cm, (Private Collection).

Lesseman

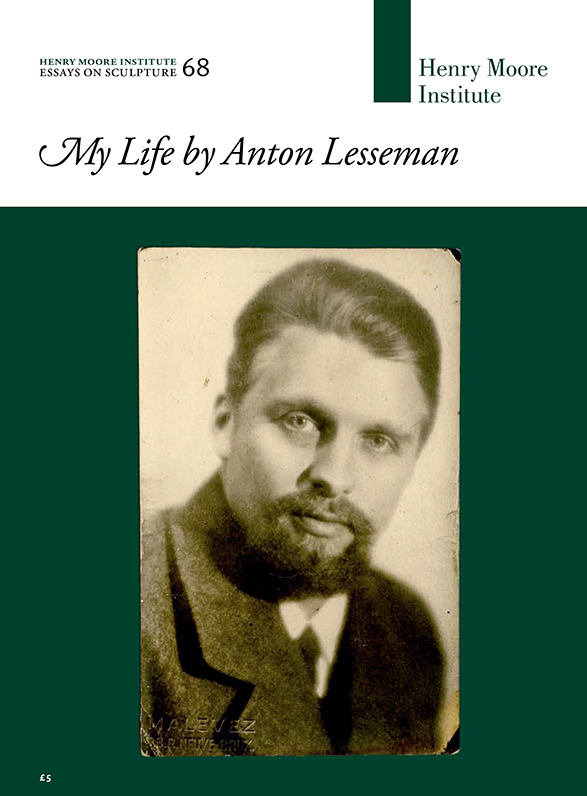

In 2013 you published a book with the Henry Moore Institute called ‘My Life by Anton Lesseman’ which documents the life and works of a fictional artist who ‘lived’ between 1899-1971. In one way this work sounds mischievous and playful – using fiction to take on the sacrosanct nature of Art History. Did any unexpected issues arise during this project? Perhaps concerning the ways Art History gets written and who is left out of the story?

I wanted to find a way in to an archive. And I wanted to use fiction to somehow infiltrate the archive. Originally, the fictional artist was going to be a woman, but it was rapidly pointed out to me that yet another man colonising a woman’s story (albeit a fictional one) would have kind of the opposite effect to what I hoped to achieve. I was keen to examine what the reverse trajectory to Henry Moore’s life and work would look like (anti-Modernist, catastrophic failure rather than a success) but also, by writing this fictional artist’s autobiography, and having them encounter some of the real figures from Moore’s circle (Betty Rea, Clare Sheridan, Gertrude Hermes etc.) I could help cast new light on some of those figures, who yes, have been left out of the story somewhat.

I made some paintings and maquettes, commissioned some other artists to make Lesseman’s work over the years (early work, mid-career, late work etc.), constructed his letters, and used some family photographs/memorabilia to make an entire bequest of his remaining estate to the HMI. I wanted to create an entry point, the possibility for other researchers to enter and infiltrate the real archive via fiction, always with that Chris Marker quote in mind: ‘If the images of the present don’t change, then change the images of the past.’

Paul Becker, 'My Life by Anton Lesseman: Essays on Sculpture 68', Book published by Henry Moore Institute, 2013.

1899-1971

Following on from this, what is it about that time period that encouraged you to insert Anton into it?

Moore was born in 1898 and I wanted them to be similar ages. I think I chose 1971 because it was the year Stevie Smith died.

Nadia Hebson, ‘Study of Adelaide Lesseman by William Coldstream’, c. 1939 (2013), oil on canvas.

Ekphrasis

You describe your collective novel ‘The Kink in the Arc’ as ‘fundamentally concerned with a version of Ekphrasis’. Ekphrasis comes from the Greek ‘ek’ (out) and ‘phrassein’ (to tell, or speak). It is a literary convention that has been used to 'translate' art works into language for two thousand years, seeking to bring images to life. What does ‘ekphrasis’ mean to you and how to you use it within your novel?

As I said, I love the idea of an artwork inside an artwork, a film within a film, a poem within a novel and the strange meetings that are thereby engendered. But I think I mean Ekphrasis usually, primarily in visual terms, which is really the whole process in reverse, starting without words and heading towards language. Certainly it is as a way of extending language and opening up the implications, the possibilities and the lives of artworks. It is a kind of mirror. I have written a lot of fictions set within moments in cinema and it goes back to my belief in the sentient nature of certain artworks, certain texts, in that they contain both thought and feeling, so, in an obviously impossible way, they can be said to lay claim to a form of sentient life. I think Kafka’s short story First Sorrow has a strange, indescribable, sentient existence. It lives! And I feel the same about that Chardin painting, The House of Cards.

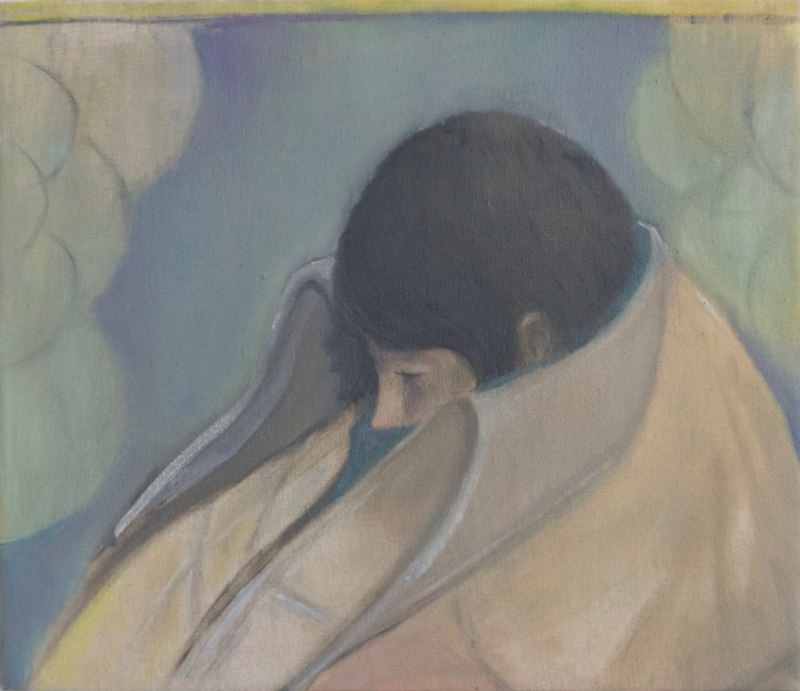

Paul Becker, 'Silhouette', 2019, oil on canvas, 27 x 22 cm, (Private Collection).

There are certain moments in Ozu when the characters have left a room and the camera continues to roll which infer that the film, its stories, its characters, its atmospheres, could, in some sense, on some plane or adjacent time, still be happening. The implications of that are that the film could play out in a different way or that a parallel fiction could seek to populate it. I just wrote a continuation of the ending of Mouchette where, yes, she rolls down the hill into the water but then she is lifted up by a great hand.

It is different again in painting, for example, wherein if you paint someone looking at a painting, then you are also painting someone thinking about painting and of course you also have the viewer, who is thinking about looking at a painting of someone thinking about and looking at a painting. It is a mis en abyme and it is a kind of device, though operating towards what end I am less sure. Perhaps it helps to untether the viewer/reader a little more, to cause her to linger, to pause and consider? I am not sure. Thomas Bernhard sometimes does this thing where he extends the idea of who is speaking so that this weird disconnect takes place. I mean lines like: ‘She told me that they had said that he wanted it not to happen’. The speaker becomes ambiguous and then where are you as a reader? It is called the Kink in the Arc because I was interested in somehow freeing the reader from the certainty of the traditional narrative arc and perhaps allowing her and the writer to share the same space: one of uncertainty, of not knowing.

Paul Becker, 'The Answer', oil on canvas, 34.5 x 39.5 cm, 2018.

Weary of the Image

Can you tell me more about the setting this collective novel takes place within; the ‘sanatorium for the weary of the image’?

I keep stressing in correspondence with participants that this space has nothing to do with mental illness and I suppose one thing I mean by that is I don’t want to trivialise mental illness or utilise the sanatorium as some sort of would-be asylum. I personally sometimes feel like I am drowning in images that are not of my own making. I don’t think that is such an uncommon feeling to have and it is not to do with, you know, “Isn’t the internet terrible!” or social media fears or whatever, or even what Herzog says about us not having adequate imagery anymore. It is more to do with my eyes seeing so much in a day that my brain can’t hope to process and all the baggage it carries with it. The idea of sanatorium is for those who need to find their own images and shed meaning that is prescribed or imposed. It is a contradiction because, perversely the sanatorium is actually filled with images; at the moment, with static artworks, paintings, prints and drawings.

The collective aspect is crucial. This shared imaginarium, this hive consciousness. Its Borgesian! Almost a hundred artists.

Paul Becker, 'Smoking and Reading', 2019, oil on linen, 40 x 33 cm.

Friends

Your practice is full of collaborations, which is quite rare for a painter. Why are you drawn to working with others and which projects have been the richest?

To go back to my 1980’s degree course, which, as I mentioned, was pretty awful, it kind of inculcated in me this weird, treasonous suspicion (alongside, concomitantly and perversely, a desperate love) of the whole project of painting and how it was this super arrogant concern in those days that was really snooty about any other way of making work. Back then we all had low level ambitions that revolved around Cork Street and the London commercial market, ‘getting a gallery’: showing and selling and that was kind of about it.

Paul Becker, 'Tutor', 2019, oil on canvas, 60 x 39 cm.

I knew I wanted to paint but I also knew I was suspicious of the white cube and the connection with the market and eventually the way I found I could deal with this (apart from hardly ever showing my work in galleries) was through my writing and how I could immediately disseminate it for free. Almost as soon as I began to write I began to work with other people. I met Francesco Pedraglio when we were both at the HMI and we have always worked together since. He’s like the dream collaborator. His urgency and energy. He is deeply critical but also hugely positive. The work I did with him and Form Content was super enjoyable. And for the last two years we have been working on a beautiful anthology with Kate Briggs, an extrapolation on her unprecedented book This Little Art (Fitzcarraldo, 2017) which gathers essays by many authors –translators, artists, editors, and poets– who relate to translation as a task that demands its own specificity.

I have been lucky mostly that my collaborators have been so amazing. My collaboration with Johannes Maier, the filmmaker was so easy because he is such a beautiful soul. The work Nadia and I did with Tess Denman-Cleaver on performances based on original translations of Robert Walser juvenilia was brilliant. Not all my collaborations have been successful. Starting a gallery called Drop City, in Newcastle ended up as an unmitigated disaster. I have made a really intense album of music with Luke McCreadie, with our band, War Dr. Only four people have heard it on Spotify but I think it’s one of the best things I have ever done. I am the guitarist and can barely play. It is just like the painting. The mistakes are the thing. How you strategize to properly redeploy them, recycle them.

Paul Becker, 'Bald King', 2019, oil on canvas, 40 x 33 cm

Future

What are you currently working on or thinking about?

I am trying to turn some of the Kink in the Arc into an actual publishable novel and am trying and failing to find an actual publisher. I understand the problem. It is a difficult project for publishers to get their heads around. I have no studio at the moment so I am drawing with coloured pencils on a small table, when my children are asleep. I miss oil painting something terrible. And showing paintings! We spoke in our correspondence regarding my moaning about the 'low level ambitions' of painters like myself in the 80’s and 90’s and you said there was 'a satisfying simplicity in making paintings and showing them that didnt have to be mercenary' which really hit home and yes, I would really love to see some of my paintings with lots of space on a wall, in a gallery. But mostly I am working on loving my two boys all day long. I have come to parenthood late in life and I find it agrees with me.